(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

When Coors introduced the first all-aluminum beverage can in 1959, it offered one cent on every can returned.

The US brewer knew it could recycle the used cans to make new cans at a fraction of the cost of virgin metal.

Recycling uses only 5% of the energy needed to convert alumina into primary aluminum and you can reprocess the stuff almost infinitely.

The used beverage can sector is now massive and today it’s possible for a used beer can to be back on the shelves in 60 days.

As the European Union prepares to toughen up its waste packaging rules to encourage a fully circular economy, aluminum is well positioned in the materials race.

A lot of recycled aluminum is used to produce alloy for the automotive sector

But the humble aluminum can also highlights the problems of achieving full circularity.

Even now, after decades of government and industry campaigns, Europe “loses” 25% of its cans every year and the United States significantly more.

Indeed, the aluminum sector as a whole loses seven million tonnes of potentially recyclable metal each year, according to the International Aluminum Institute.

Fully closing that scrap gap is not going to be easy but it will be essential for the sector to decarbonise.

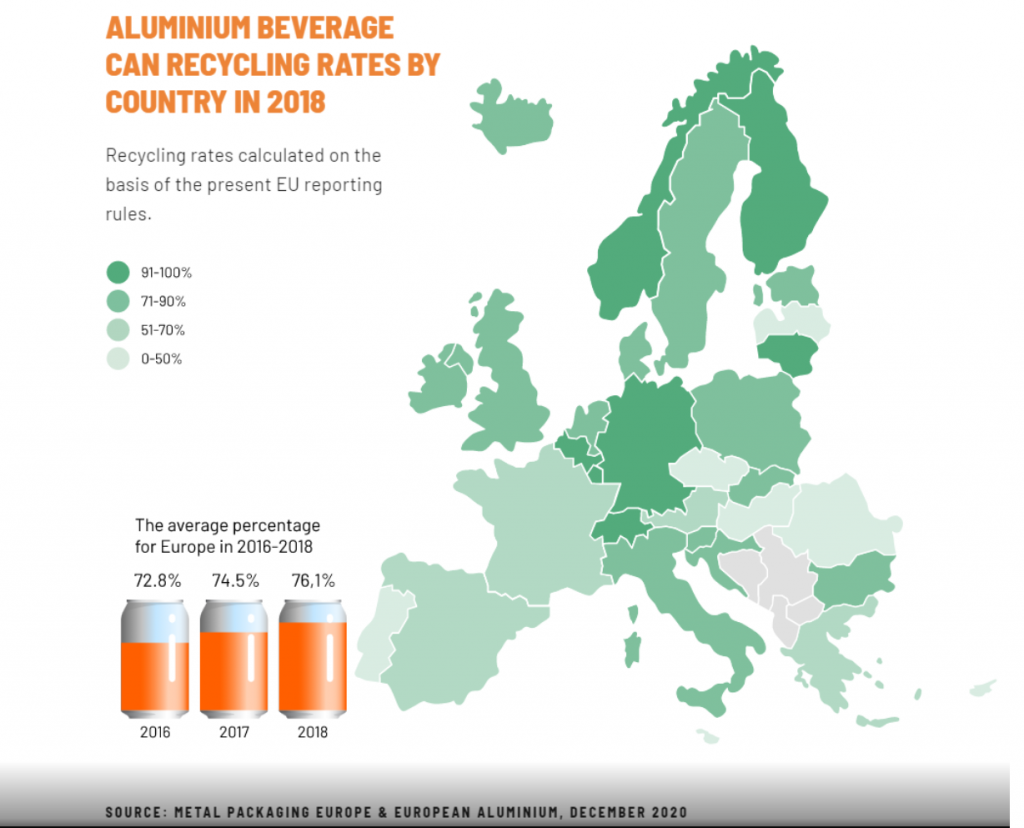

The aluminum can recycling rate in the EU, including Britain at the time, and Switzerland, Norway and Iceland was 76.1% in 2018, according to European Aluminum.

The rate has been steadily rising in recent years and might be viewed as a success story but not by the European Commission, which wants 100% recyclability as part of its circular economy action plan.

The current recycling rate amounts to a less-than-optimal 25% material loss from each used beverage can cycle, noted Kestutis Sadauskas, Director for Circular Economy and Green Growth at the European Commission’s Directorate General for Environment.

He was speaking at the launch on Wednesday of a joint campaign by European Aluminum and Metal Packaging Europe to achieve 100% regional can recycling rates by 2030.

One country, Norway, has already got close thanks to a pioneering deposit return system (DRS) and a ban on multi-material packaging. It collects over 90% of cans through DRS and another 6% through sorting of household waste, according to Kjell Olav Maldum from Norwegian deposit return system INFINITUM.

Indeed, those European countries with higher recycling rates tend to have some form of DRS in place.

The European Commission has rejected harmonised DRS in the past but is looking at the idea again, according to Sadauskas. So too is the French government as it tries to lift the country’s relatively low recycling rate of 66%.

DRS can move the dial fast towards 80% return levels, INFINITUM’s Maldum said.

But to get to 100% closed-loop status across Europe will require a full supply-chain response including eliminating multi-material packaging, improving collection systems, working with “informal” recyclers in poorer East European countries and, above all else, doubling down on consumer awareness.

It’s worth remembering that the aluminum can is the poster child for recyclability dating back to those first Coors’ two-piece cans.

But after decades of telling the public to not throw them away, around a quarter of Europeans are still doing exactly that and a lot more in some countries such as Portugal, where the recycling rate was just 43% in 2018.

The metal loss is higher in the United States, where the Aluminum Institute estimates a 2019 industry can recycling rate of 55.9% and a consumer recycling rate of 46.1%, both down on 2018 levels.

The International Aluminum Institute (IAI) reckons that globally 1.2 million tonnes of aluminum in the form of used beverage cans and other rigid packaging was not collected at end of life in 2018.

That’s more than the United States’ annual primary aluminum production.

It is ironic that aluminum, a metal so central to the green revolution, risks not being able to grow sufficiently because of the pressure to decarbonise

“Across all segments, around seven million tonnes of aluminum is not recycled every year due to collection and processing losses at the end of its life, and this will rise to 17 million tonnes per annum by 2050 with no change to current recycling rates,” the IAI notes. (“Aluminum Sector Greenhouse Gas Pathways to 2050, March 2021)

Some sectors such as construction have very high recycling rates but also very long lifetimes, which means that around three quarters of the 1.4 billion tonnes of aluminum ever produced is still in service.

This constrains the amount of recyclable material in circulation. But clearly there remains a big scrap gap in the supply chain centred on packaging and consumer products.

Moreover, the aluminum recycling sector is facing another big headwind.

A lot of recycled aluminum is used to produce alloy for the automotive sector, where the metal’s combination of strength and lightness is perfect for housing the engine.

But the entire European auto sector is now pivoting away from the internal combustion engine towards electric vehicles. The aluminum in the current automotive fleet may be in a form of alloy that is simply redundant when it comes to the recycling stage.

Driving can recycling to 100% levels may be the easy part of the broader circular aluminum equation.

Lifting the recycling rate is not just about the growing political imperative towards sustainability but it could also hold the key for the whole aluminum sector.

The power-intensive smelting process means that aluminum accounts for around 2% of all global greenhouse gas emissions with much variability depending on energy source.

A path to net zero carbon is going to be challenging, particularly given the fact that China, the world’s largest producer, is heavily dependent on coal for its aluminum production.

Energy and emission stresses in the country’s aluminum sector are already starting to appear in the form of mandated curtailments in the province of Inner Mongolia.

It is ironic that aluminum, a metal so central to the green revolution, risks not being able to grow sufficiently because of the pressure to decarbonise.

Recycling with its low carbon footprint offers an obvious answer. It can’t fully offset the need for more carbon-heavy primary production but it can determine how much new capacity the world needs.

The IAI forecasts that an extra 25 million tonnes of primary capacity will be needed to meet an expected 80% rise in demand by 2050.

That assumes a 100% aluminum recycling rate. Miss it and the world will need yet more energy-hungry smelters. Every can literally counts in terms of meeting future demand.

It’s worth bearing in mind the next time you finish a drink and look around for somewhere to throw the can. Particularly if you’re in the aluminum business.

(Editing by Susan Fenton)

Comments