(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

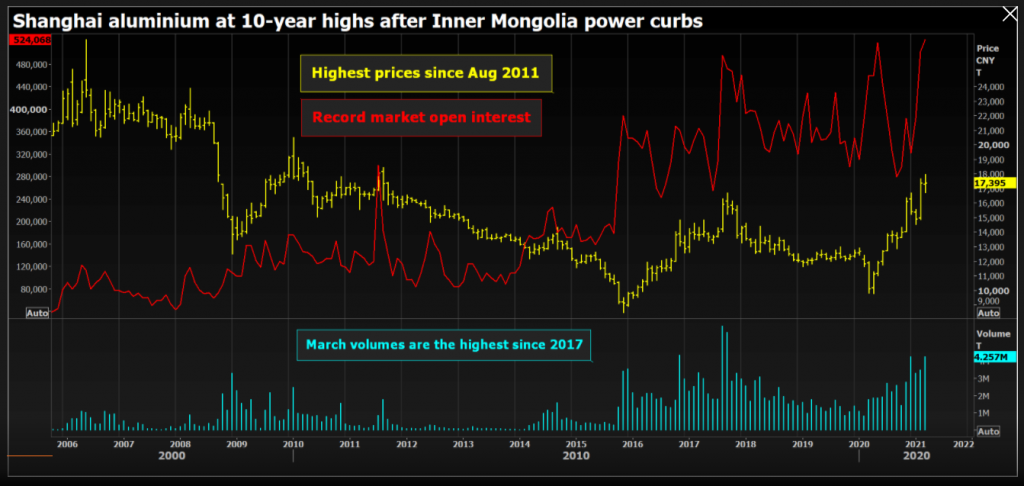

Shanghai aluminum prices have this week powered to their highest level since August 2011.

This month’s volumes on the Shanghai Futures Exchange’s aluminum contract are already the highest since 2017 and market open interest is at record peaks.

The surge in speculative activity follows the mandated curtailment of smelting capacity in the city of Baotou in Inner Mongolia, as the provincial government tries to meet its quarterly energy targets.

The suspensions are small, at around 200,000 tonnes of annualised capacity, according to Citi analysts. That’s not going to make much physical market impact when China’s national aluminum output production surged by 8.4% in the first two months of the year.

But the significance is the direction of travel. China is embarking on the road to decarbonisation, a journey that poses hard questions of a power-hungry sector such as aluminum smelting.

Inner Mongolia’s energy problems may be the harbinger of future waves of “green” disruption in the Chinese aluminum market.

Inner Mongolia was one of three provinces which failed to meet targets on energy consumption and efficiency over the first three quarters of 2020, according to Citi (“Metals Weekly”, March 17, 2021).

It is now preemptively mandating energy cuts to industrial users, including aluminum smelters. A handful have taken small amounts of capacity off line for maintenance.

The measures are expected to be short-lived but there’s the distinct possibility of future rolling curtailments if quarterly targets are threatened.

Moreover, Inner Mongolia has capped its energy consumption growth over the next five-year plan, placing in doubt planned expansions such as the 400,000 tonne per year Baiyinhua project, Citi notes.

The province may have reached its de-facto aluminum capacity limit based on energy consumption, with the existing 6.9 million tonnes of capacity now vulnerable to the vagaries of quarterly targets which are only going to tighten incrementally over time.

It’s worth noting that another province to fail the test was Ningxia, which has 1.2 million tonnes of aluminum smelter capacity. There has been no word of curtailments in Ningxia, but it’s a further warning that power consumption constraints are going to be a recurring theme in the Chinese aluminum sector.

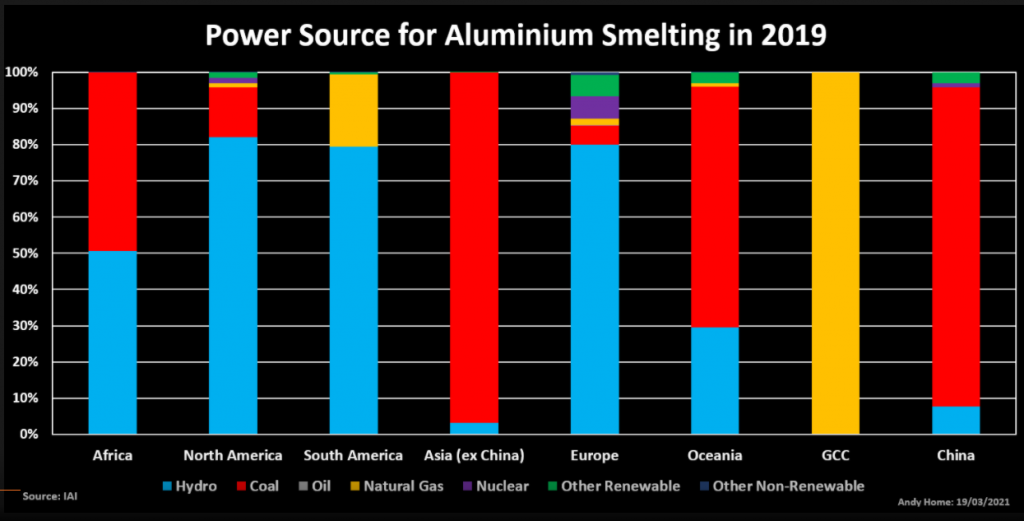

The sector’s fight for its share of China’s energy market is complicated by the fact that so many smelters use power derived from carbon-intensive coal, either via the national grid or more often in the form of captive power plants.

China produced 36 million tonnes of primary aluminum in 2019 and used 484,342 gigawatt hours of energy to do so, 88% of which was derived from coal, according to the most recently available information from the International Aluminum Institute (IAI).

There has been a significant relocation of capacity over the last two years to Yunnan province, which boasts lots of green hydro power. That should lift the proportion of hydro in the national power mix from a low 7.7% in 2019.

But not everyone will be able to squeeze into hydro-rich provinces such as Yunnan and Sichuan.

Most of China’s smelter sector is going to remain dependent on coal for its energy, which stores up trouble for a country now committed to carbon neutrality by 2060.

Inner Mongolia’s curtailments presage the bigger trade-offs to come.

The power-intensive smelting process accounts for around 75% of aluminum’s cradle-to-gate emissions footprint, according to the IAI.

It is also the segment of the value chain that has the greatest variability depending on the source of the power used.

The carbon footprint of primary aluminum can span a wide range from less than 5 tonnes of carbon equivalent for renewable energy such as hydro to more than 25 tonnes for coal.

China’s smelters are evidently struggling to keep up with demand from the country’s huge semi-manufactured products sector

Globally, the aluminum sector must cut its emissions by 77% by 2050 to meet climate goals, the IAI said in an analysis of the decarbonisation challenges ahead. (“Aluminum Green House Gases: Pathway to 2050,” March 2021)

Decarbonising the power used to convert alumina into metal in the smelting process is the single biggest lever to reduce emissions.

The twin drivers of change for coal-dependent countries such as China will be a broader move away from fossil fuels towards renewables in the national grid and the use of carbon-capture technology for captive plants, the IAI said.

“Depending on the pathway(s) followed, the capital investment required for electricity decarbonisation is in the range of $0.5-$1.5 trillion over the next 30 years”, it warned.

Quite evidently, the highest costs will be borne by coal-dependent smelters.

The challenge to decarbonise the aluminum supply chain is compounded by the fact it will need to grow by an extra 25 million tonnes to meet demand by 2050, according to the IAI.

China has been the driver of primary production growth this century, to the point that the country now accounts for around 58% of global production.

Another three million tonnes of capacity is expected to come on line this year, but that brings national capacity close to or even over Beijing’s 45 million tonne cap.

China’s 20-year aluminum juggernaut is running out of road.

It is now clear that in provinces such as Inner Mongolia even maintaining existing capacity is going to be challenging as China looks hard both at its overall energy consumption and its energy mix.

It’s noticeable that while Shanghai prices surged to decade highs this week, the London Metal Exchange price managed only a three-year peak of $2,249.50 per tonne, and that only briefly.

The Inner Mongolia cutback news has fed into an existing bull narrative in China centred on the stellar rebound in metals demand since covid-19 lockdowns a year ago.

The country continues to suck in primary metal, importing 455,000 tonnes of unwrought aluminum in the first two months of 2021.

Prior to last year China hadn’t imported so much metal since 2009-2010.

China’s smelters are evidently struggling to keep up with demand from the country’s huge semi-manufactured products sector.

Such domestic supply-chain stress is a rare phenomenon, but it’s going to become more frequent as China’s green policies start reshaping both the power and aluminum production sectors.

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

Comments