(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The London Metal Exchange’s (LME) proposal to end 144 years of open outcry trading is running into opposition from both brokers and industrial users.

The iconic red-leather trading ring has been suspended since March last year due to COVID-19 social restrictions, with the generation of the LME’s benchmark base metal prices being conducted on screen.

The exchange has hailed what it views as improved liquidity and transparency in the price discovery process, and in a wide-ranging January discussion paper dropped the bomb-shell that it was seeking views on closing the ring permanently.

A push-back by LME traditionalists is now gaining momentum. The LME’s analysis around its proposal to end open outcry has been queried.

The exchange has responded by releasing more data, including previously unpublished information on the number of objections to the pricing process.

Resistance from some of the nine LME ring-trading brokers was always to be expected. Potentially more worrying for the exchange is that its industrial customers aren’t happy either.

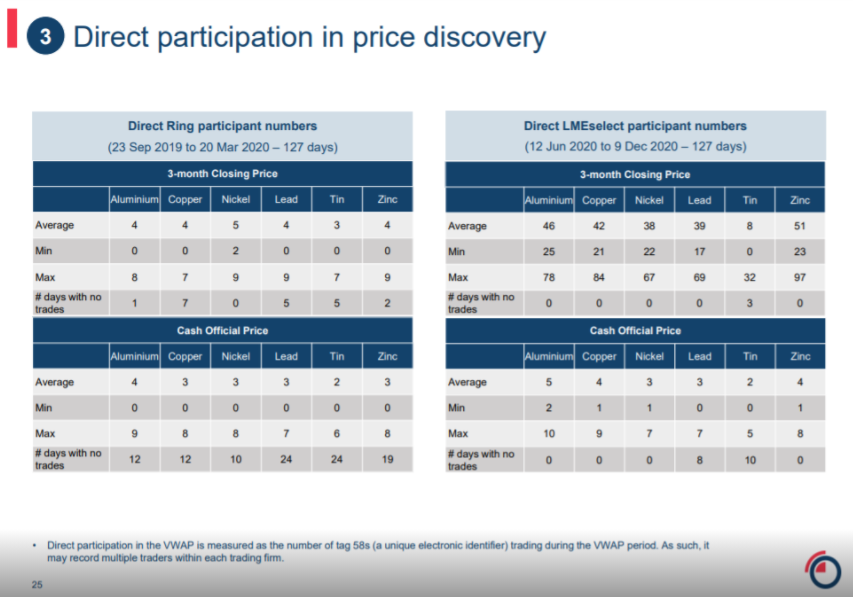

The LME’s core position is that volumes and participation in the two daily pricing sessions – the midday “officials” and the late-afternoon “close” – measurably improved in the 127 days after the March transition to electronic trading relative to the period before.

Some brokers feel the LME is using too narrow a metric, pushing it to release a more holistic view of volumes and, for the first time, the number of price objections.

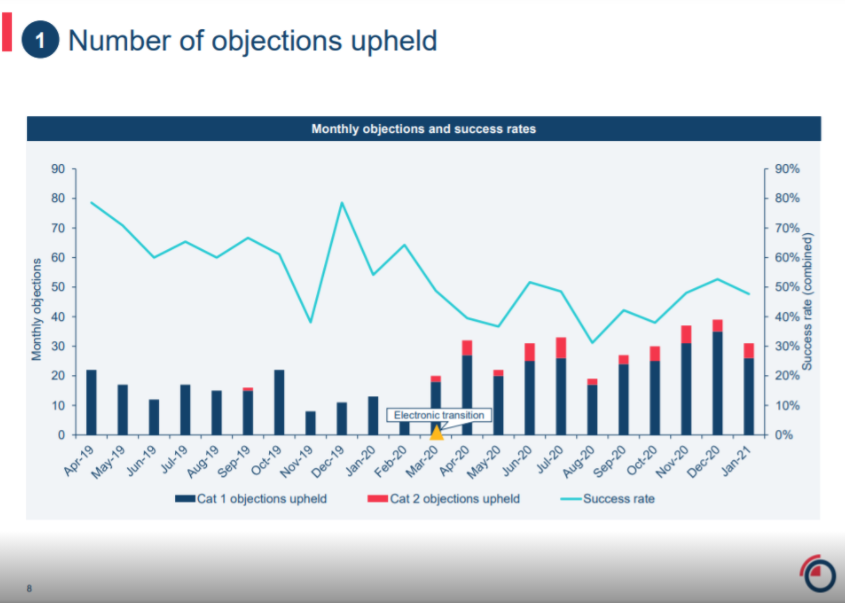

Objections are part and parcel of the LME’s price discovery process, with the exchange’s Operations Team ruling on whether a price stands or, if the objection is upheld, needs to be revised.

Such price queries have risen sharply since the move to electronic price discovery but, as the LME points out, so too have the number of participants in the pricing period.

The feedback window for the LME’s discussion paper closes on March 19, with a formal response due by the end of the second quarter

Prior to its suspension, ring-trading was by definition limited to the nine brokers operating in the red-leather circle. Since last March the number of participants in the electronic “closing” session has been as high as 97 in the case of zinc.

More players and a more actively traded curve would be expected to lead to more objections, and it’s noticeable that the ratio of successful queries hasn’t dramatically changed.

The problem is that the statistics can be argued both ways, as can the extra volume datasets published.

The LME market is highly complex, comprising open outcry, screen and inter-office trading channels as well as curiosities such as “basis ring” trades, priced on, but not traded on, the rings.

No-one’s even sure what’s happened to the “basis ring” trades in the last year. The LME thinks the business has migrated to the inter-office market, but doesn’t have enough information to track the transition.

The statistical waters can be very muddy when it comes to LME volumes, and the release of all this extra data is probably only going to muddy them more.

More fundamentally, any volume comparison assumes like-for-like market conditions, which is simply impossible.

It’s worth remembering that the suspension of the ring in March last year coincided with base metals turbulence as prices pivoted from meltdown to recovery. Before and after were not the same.

It’s also worth highlighting that this statistical debate is almost exclusively focused on the LME’s “closing” prices, which are used to mark positions to market and set overnight margining rates.

Financial players view them as the day’s most important reference price, which is why so many are now participating in the electronic closing session.

None of them, however, is much interested in the “official” prices set in the midday session.

The average number of participants in these sessions after the move to electronic pricing was unchanged in the case of nickel, lead and tin, and increased by only one in the aluminium, copper and zinc sessions.

Participation relative to the closing session is much lower. The highest number of participants after the ring’s suspension was just 10, compared with nine before.

However, these “official” prices matter a lot to the exchange’s industrial users, who have embedded them into their physical contracts.

And parts of that industrial spectrum are also pushing back against the closure of the ring.

German metals association VDM publicly warned that “the forcing of trades on to the electronic system is questionable, as trading there is heavily influenced by algorithmic and high-frequency trading”.

The VDM’s 220 or so members typify the metallic backbone of the LME’s user-base and the association’s opposition is politically difficult for the exchange – particularly if other physical customers are saying the same privately.

The feedback window for the LME’s discussion paper closes on March 19, with a formal response due by the end of the second quarter.

The fate of the ring has been a hot topic for many, many years in the base metals trading community, but until now no-one’s explicitly queried its existence.

It’s difficult to predict how many will join the resistance or how many would be needed to persuade the LME to stay its hand.

Is it possible that there is a third option?

It’s clear that some of the core ring-trading community want to keep open outcry. It’s also clear that at least part of the industrial user base want the same, particularly when it comes to generating the midday “official” prices.

How these particular prices are determined doesn’t seem to be of much interest to the broader investor community, which has embraced participation in the closing sessions.

The market’s industrial and financial components are pulling in opposite directions, meaning one side will be unhappy whatever the LME decides.

Could ring-trading continue but in an ancillary, rather than central, role in the LME’s fluid ecosystem?

The concept of a break-away ring servicing the more complex needs of the physical supply-chain was mooted several years ago, when LME traditionalists and modernists were locked in a similar battle over the market’s optimal structure.

The Nonferrous Metal Exchange was intended to complement, not challenge, the LME to the point of potentially using its clearing infrastructure.

It never got off the drawing board, but it might be time for LME traditionalists to dust down the old plans.

And if you think the idea of ring-trading version two is far-fetched, remember there is already a second LME trading ring.

The exchange’s “disaster recovery” ring is located some 50 kilometers east of London in Chelmsford in Essex, the home county for generations of LME floor traders, including the current one.

Anyone for the Essex Metal Exchange?

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

Comments