(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Clyde Russell, a columnist for Reuters.)

China has almost single-handedly rescued commodity markets throughout the global coronavirus pandemic, but there are signs that its appetite for imports is levelling off, albeit at robust levels.

November trade data released on Monday painted a largely steady picture, with imports of major commodities showing only relatively minor changes from both month earlier, and year earlier comparisons.

This isn’t to say that China’s commodity demand is faltering, far from it. Rather it appears that demand growth is moderating and imports may tend to stay around current levels, rather than show some of the dramatic increases from earlier in 2020.

Overall, there are signs that China’s imports of major commodities are plateauing

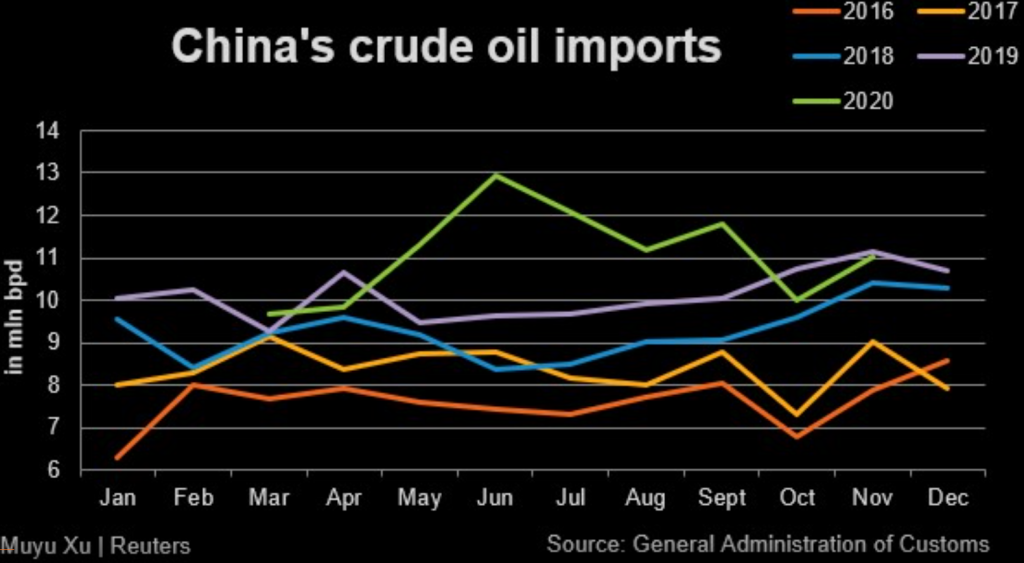

Crude oil imports were 45.36 million tonnes in November, equivalent to 11.04 million barrels per day (bpd), up from 10.02 million bpd in October, but down from 11.13 million bpd in November 2019.

The November figures were likely boosted by the clearing of the last of the backlog of cargoes ordered during the brief price war in April between top exporters Saudi Arabia and Russia, which saw benchmark Brent crude futures drop to the lowest in 17 years.

Chinese refiners took advantage of the fire sale in crude prices to stock up, so much so that tankers were waiting for up to several months to discharge cargoes at clogged ports.

But with the flood of crude now over, it seems more likely that import demand will settle into a range of between 10.5 million bpd to 11.5 million bpd per month.

This is higher than the level that prevailed prior to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus at the start of the year, and is mainly a reflection of the addition of new refining capacity in China this year.

Tuning to copper, another metal whose fortunes this year have been closely linked to China’s demand, and again there are signs of demand starting to moderate.

November imports of unwrought copper were 561,311 tonnes, down 9.2% from October’s 618,108, but up 16.2% from 483,000 in November last year, according to customs data.

November marked a six-month low for copper imports, and the second consecutive monthly decline, but this has to be viewed in light of the extreme strength in copper imports earlier this year.

In the first 11 months of 2020, unwrought copper imports were 6.17 million tonnes, up 38.7% from the same period last year.

Part of the drop in November imports is likely because the arbitrage window between London and Shanghai prices closed, meaning traders would find it less profitable to move copper into China.

But it’s also likely that China now has sufficient copper available to meet domestic demand, which has been boosted by the government’s stimulus efforts that drove copper-intensive activities such as housing construction and infrastructure.

Iron ore, like copper, also saw a drop from October, but November imports of 98.15 million tonnes were up 8.3% from the same month last year.

The steel-making ingredient has been another standout this year, with imports in the first 11 months reaching 1.073 billion tonnes, up 10.9% from the same period in 2019.

Iron ore is another commodity reflecting the impact of China’s stimulus spending aimed at boosting the economy after the hit caused by lockdowns to combat the spread of the coronavirus.

Coal is the exception to the resilience of China’s commodity imports, but the weakness is the result of policy decisions rather than a reflection of weaker demand.

Coal imports were 11.67 million tonnes in November, down 15% from October and 20.8% from November last year, while imports for the first 11 months are 10.8% below the level for the same period in 2019.

China has restricted imports from top suppliers Indonesia and Australia, most likely as part of efforts to protect the domestic mining industry, but also in Australia’s case as part of Beijing’s ongoing dispute with Canberra over a variety of political and trade issues.

Overall, there are signs that China’s imports of major commodities are plateauing.

To make a bullish case for further gains in coming months, the argument would have to be for an increase to the existing stimulus spending, or an acceleration in domestic or foreign demand for Chinese products.

(Editing by Richard Pullin)

Comments

Ray Muskett

Time to get over the cave incident and forget about it.