President Xi Jinping’s surprise announcement that China plans to go carbon-neutral by 2060 has left many questions, none more important than: “How?”

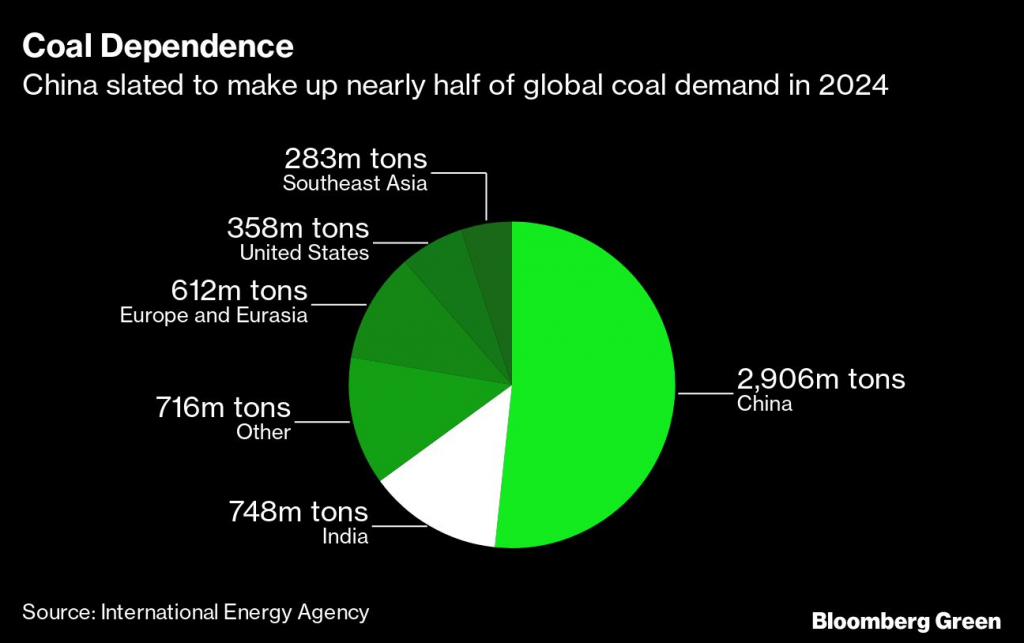

China is the world’s largest energy user and greenhouse gas emitter, mines and burns half the world’s coal, and is the top importer of oil and natural gas. Transitioning that economic behemoth to carbon-neutrality within a few decades could cost $5.5-trillion, Sanford C. Bernstein & Co estimates, and require the deployment of technologies that are barely in use today.

“What’s being contemplated here has never been done before,” said Neil Beveridge, an analyst at Bernstein. “The larger the energy mix, the longer it takes to transition. This is a monumental challenge.”

While Xi’s comments during his speech to the United Nations on Tuesday were void of details, he did said China would scale up its Paris Agreement commitments through “more vigorous” measures. China may provide more details about its new climate strategy in an official submission to UN later this year, said Chai Qimin, a government researcher affiliated with the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

In the meantime, analysts see a few clear angles China must take to hit its target. And those will likely to be laid out in the country’s main development blueprint — the five-year plan. Its 14th version, under discussion by policy makers now, will be released next year and set an economic and energy course for 2021 to 2025.

“If any country can achieve such ambitious goals it will be China,” said Gavin Thompson, Asia-Pacific vice-chairman at consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “Strong state support and coordination have proved extremely effective at reaching economic goals; if this is now directed towards climate change then China is capable in transforming its carbon emissions trajectory over the coming four decades in exactly the same way it has transformed its economy over the past 40 years.”

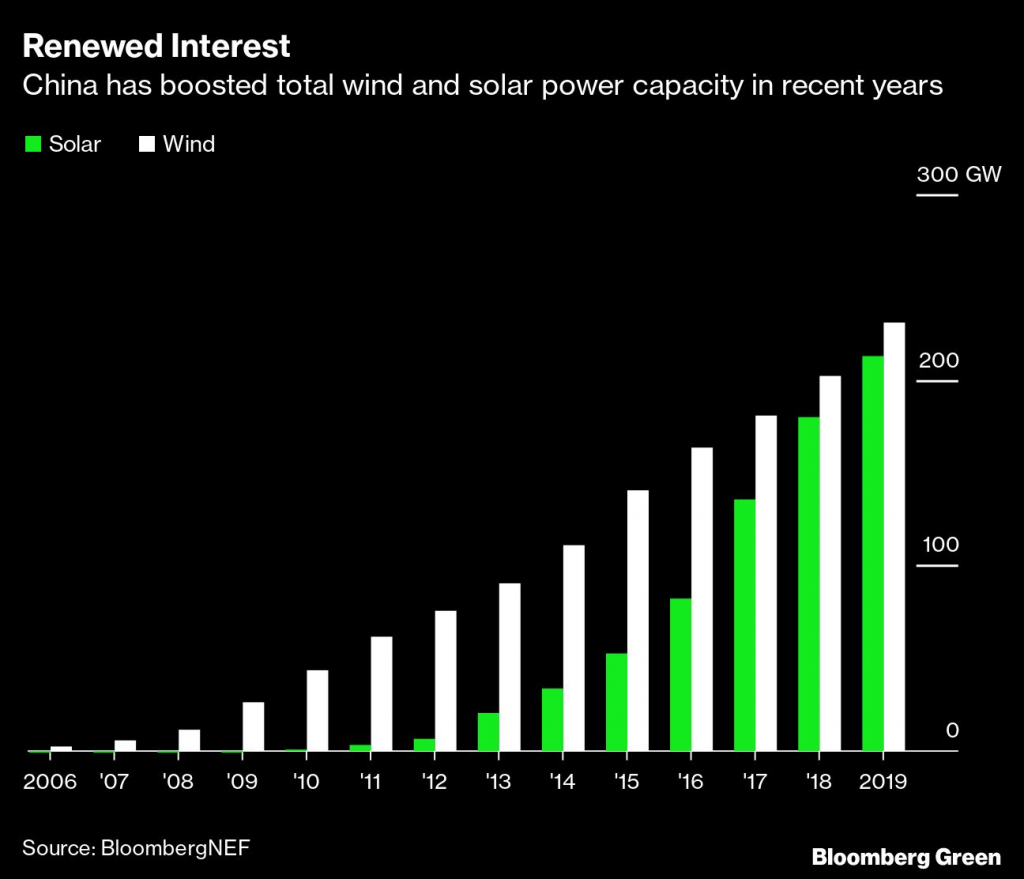

Non-fossil fuels, which account for about 15% of the country’s primary energy mix now, will have to take a huge leap forward. China had about 213 gigawatts of solar and 231 of wind power capacity installed at the end of last year, according to BloombergNEF. That will have to increase to at least 2 200 GW of solar and 1 700 of wind by 2060 to make the transition, said Xizhou Zhou, vice president for global power and renewables at IHS Markit Ltd.

China is already considering proposals to accelerate its adoption of clean energy as part of the next five-year plan and Xi’s speech further affirms that direction, said Robin Xiao, an analyst at CMB International Securities. The push has the added benefit of supporting domestic industry, as China is home to some of the largest solar and wind companies in the world.

Other carbon-free sources, like nuclear power, will also have to increase. China’s first homegrown reactor recently began loading fuel, and the country has started approving new plants after a freeze that lasted several years.

The increase in renewables would mean a reduction in fossil fuels from about 85% of the energy mix now to 25% or less, according to Bernstein, which earlier this week published an estimate that net-zero carbon by 2050 would cost $180 billion annually. It sees oil and coal bearing the brunt of the reduction, with cleaner natural gas posting modest growth from its relatively low current levels.

The biggest hit would land on coal, the most polluting fossil fuel, which accounted for nearly 58% of China’s energy in 2019. In one of the more ambitious climate outlooks prepared by a State-owned energy giant, China National Petroleum Corp. last year forecast a “Beautiful China” scenario with coal at only 14% of the mix by 2050.

That would be a reversal of China’s current path of adding capacity both in coal mining and in coal-fired power plants. It would also have a major impact on employment in a country where coal mining and washing employs about 3.5 million people and provides abundant, cheap fuel for the world’s second-biggest economy.

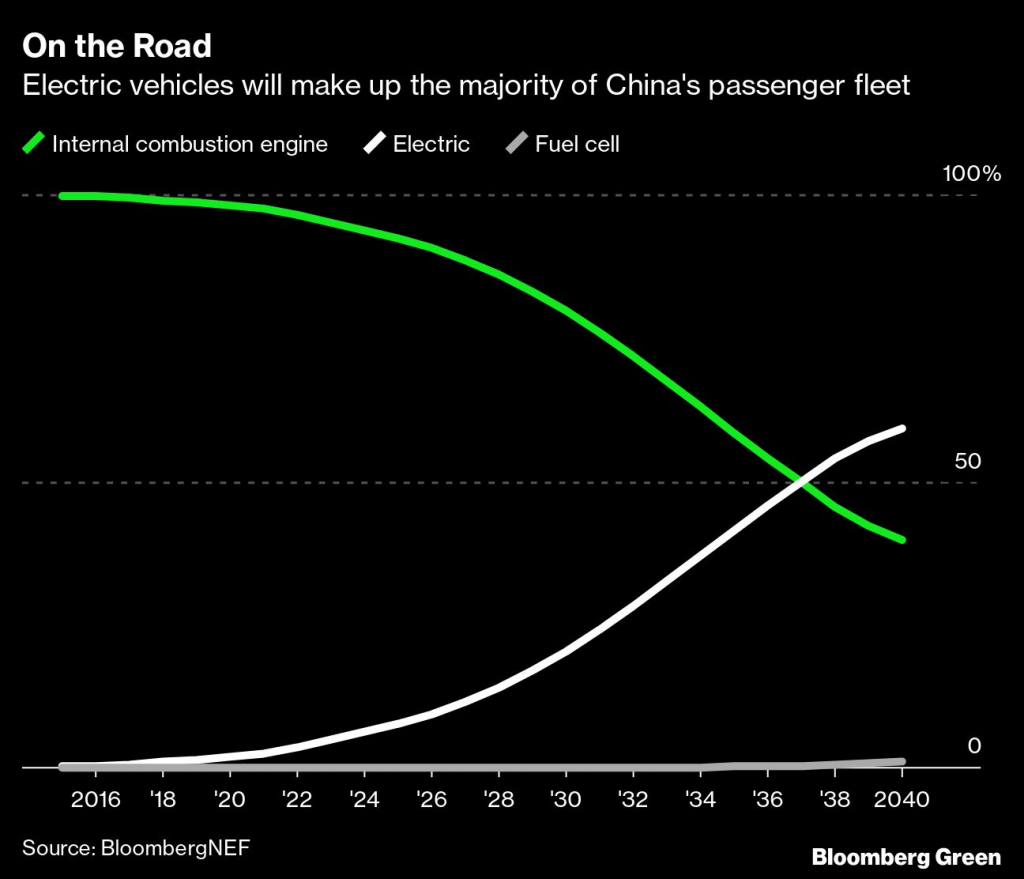

A switch from gasoline and diesel guzzlers to electric vehicles is also vital to zeroing out emissions, and it’s one that’s already underway. BNEF analysts expect there to be more electric vehicles on China’s road than internal combustion engines by the mid 2030s.

Outside of reducing emissions, that has two side benefits for China. It reduces what is now the world’s biggest import bill for crude oil. And, while China had to play catch-up with the rest of the world in traditional car manufacturing, it’s now a leader in electric vehicles.

Hydrogen produced from renewable energy — a relatively minuscule and expensive part of the energy mix called “green hydrogen” — will have to scale up and become cheaper to help decarbonize industrial sectors too energy intensive to run on electricity, such as steel production, which China dominates.

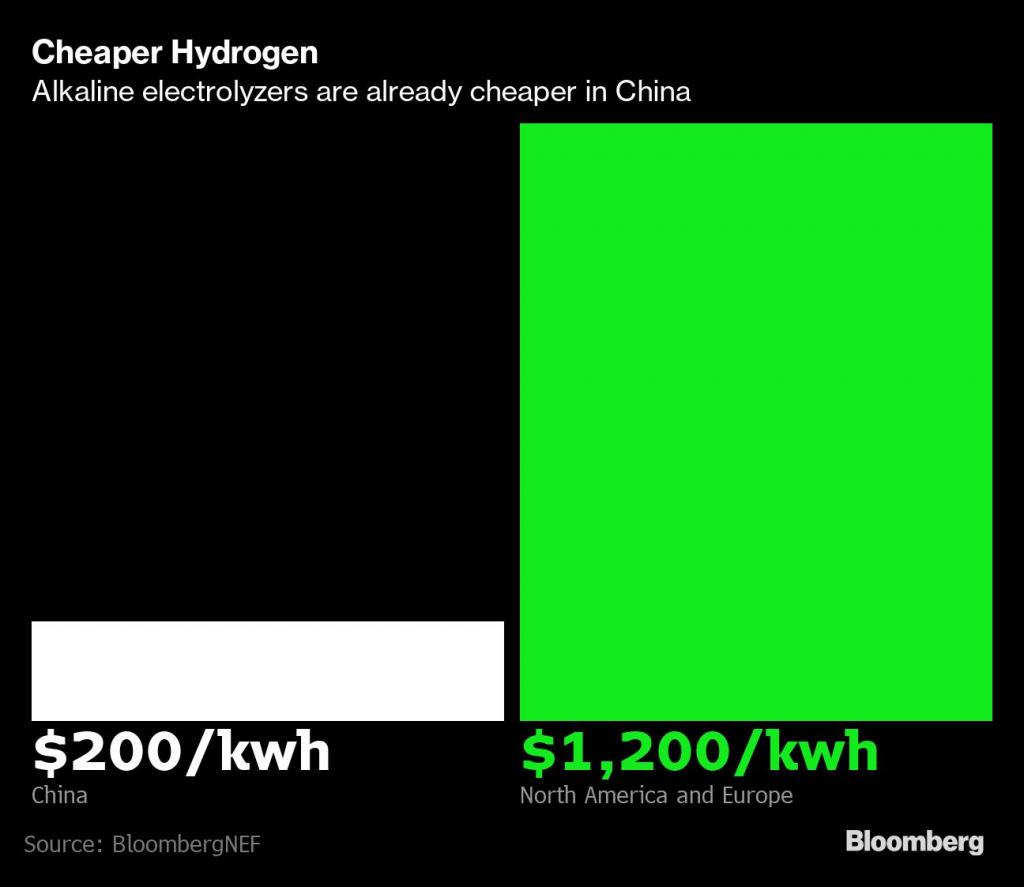

China has been increasing its research budget in the technology, from $19 million in 2015 to $129 million in 2018, according to BNEF. It also has the lowest-cost electrolyzers in the world, which produce hydrogen from water.

If fossil fuels don’t fall to zero, China will have to find ways to offset its remaining emissions. One possibility is carbon capture and storage, a relatively immature technology that’s little-used today because of high costs and virtually no economic benefits. If that changes, perhaps from the rising price of emissions in China’s fledgling carbon market, the technology could advance and be paired with coal or gas power plants.

China could also use other offset programs, such as the “nature-based solutions” it committed to last year at a UN summit, which entail large-scale tree planting and wetland restoration. For example, China plans to create 35-million hectares of forest by 2050 for its “Great Green Wall” project.

(With assistance from Feifei Shen, Jing Li and Kathy Chen)

Comments