After a century of Western oppression followed by the most broadly-encompassing civil and interstate war in African history, it should come as little surprise that the DRC is not yet a functioning democracy. The nation is rife with corruption, poverty and failing infrastructure. However, it also holds half the world’s cobalt and vast copper deposits, in addition to some 1,100 other mineral resources as estimated by the World Bank. The tremendous mineral wealth of the DRC has kept the operations of mining powerhouses such as MMG and TFM running despite the challenging environment, but few new players have entered the market in recent years. For investors, the situation is a high-risk, high-reward dilemma in which the feasibility of doing business in the DRC constantly hangs in the balance. The latest potential tipper of the scale is the new mining code.

The new mining code is the result of a turbulent legislative saga. Following popular demand for reform, the previous mining code was introduced in 2002 with the objective of invigorating the mining sector in the aftermath of a long civil war. The law – offering universally applicable tax rates, a first-come, first-served licensing system and a stabilization clause guaranteeing 10 years of maintained provision after permitting – achieved its goal of attracting foreign investors and the ramping up of cobalt and copper production. However, the real gains of the Congolese people were difficult to detect, leading to the initiation of a reform process in 2012 that would aim to allow the DRC to capture a bigger slice of the pie. In 2015, the suggested changes were submitted to parliament, but the process was suspended due to crashing commodity prices. After a lengthy reform process, marked by predictable deadlocks between the government and mining companies, former President Joseph Kabila finally signed the modifications into law in March 2018.

The major mining houses were concerned less over the profit tax provisions as they were by the steep royalty hike as well as the slashing of the stabilization clause from 10 to five years. “The amendments to the stabilization clause frustrated many of the big companies as the 10-year stability clause had formed the basis of many investment decisions in the country,” said Louison Kiyombo, partner at global auditing firm KPMG. “This period of stability resulted in over US$10 billion in direct investments by the mining industry and created some 20,000 full-time jobs.”

While sudden regulatory changes will always cause a certain outcry from the mining sector, the DRC mining code was bound for change as the previous version was tailored to the country’s immediate post-civil war situation. Today, as the near-laissez faire regulation of the previous mining regime has served its purpose, there are likely long-term benefits for not only the country, but also the mining sector in granting the DRC a more generous chunk of the profits. “Often, resource nationalism is driven by a combination of lack of state revenue and government perception that the country is not obtaining a fair share of resource rents ,” said Peter Leon, global cochair Africa at London-based law firm Herbert Smith Freehills. “When commodity prices increase, a significant number of African countries do not have the mechanisms to benefit as long term concession agreements often contain fiscal stabilization provisions. Resource nationalism is cyclical as much as it is contagious.’’

In a country like the DRC, where some two thirds of the population live below the poverty line, popular discontent can rapidly degenerate into dissent and force the leadership towards extreme legislative measures. Thus, Kabila’s triumph in the governmentindustry showdown might just work to undermine the risk of more drastic future changes, such as the recent protectionist regulation enacted in Tanzania. Moreover, the new regime does not position the DRC as a regulative outlier. Both Ghana and Cameroon collect the same 35% profit tax, and neighbors such as Zambia, Tanzania and Ghana impose copper royalty taxes within the same range. A more controversial part of the mining code, however, is the subcontracting law. Entered into force in March 2017 with a one-year transitional period, the law establishes incompletely – and rather confusingly – that subcontractors must be Congolese and owned by Congolese shareholders. The confusion is born of the inadequate specification of “subcontractor,” which in French – “sous-traitance” – is used generically for all contractors rather than just “subcontractors,” which would otherwise be interpreted as a contractor hired by another contractor. Whether this is true in a Congolese context is yet to be explained by the government that has limited the definition to “a service contract, consensual, onerous and written.” The law, meant to “promote small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with Congolese capital, to protect the national labor force,” is commonly accepted – although without certainty – to compel majority Congolese ownership of contracting firms.

Definitional issues aside, the legislation brings both possibilities and potential issues, the chief ones encapsulated by Samuel Opare, managing director at mining contractor NB Mining Africa, who stated: “The new subcontracting law will create additional capacity for local companies which have lacked sufficient capital to take on projects. As a consequence of the new law, these companies can now find a foreign partner willing to fund a project while they act as a local partner to meet legal requirements.” He continued to explain that there is a risk of the local owner does not contribute in other ways than ensuring requirements are met on paper. Therefore, Opare suggests, “the new laws should be coupled with government financial support to local companies which would allow them to level with foreign competition.”

Weighing in on the issue, Freddy Kitoko Nyembo, chairman at sustainable investment platform Investissement Durable au Katanga (IDAK), described the issue as bilateral, where many Congolese citizens are willing to take a backseat while collecting profit, and many expat companies are willing to exploit the situation. “For the law not to be rendered futile, we need proper enforcement mechanisms where companies claiming to follow the subcontracting laws are scrutinized by independent inspectors,” Nyembo said. In addition, Djo Moupondo, CEO at human resource management firm Sodeico, said that while he believes the regulation could significantly benefit the development of the country, the transition period of one year is too short: “The issue primarily lies with the difficulty to acquire skilled technical labor in the DRC. Companies are now using local providers to be on the good side of the law, but these local providers often lack the appropriate expertise, which undermines safety in the mines. If the government implemented an adequate transition period, there would have been the possibility for the necessary transfer of skills and to form partnerships.”

In the absence of clarification of the law, the Congolese may simply perceive subcontracting as a too complex and rigid process that would render the law counterproductive. However, should the regulation be adequately explained and properly enforced, it could benefit both the Congolese population and international mining companies as it would produce local expertise in the long term.

As the dust settles after the mining code scuffle, mining companies – some that initially threatened legal action against the government – have no better alternative other than to conform to the new legislation if they wish to continue their operations. In an act of strategic muscle flexing, former President Kabila invited leaders of major mining houses to discuss the bill, after which he immediately declared nothing in the code was subject to change. While mining companies could still challenge the decision in court, lengthy legal processes are likely to render them disinclined to such decisions. Perhaps more importantly, companies’ decisions to stay operational will always depend on profitability. Considering the mining code largely conforms to regional standards, while the more immoderate aspects such as the 50% super tax are offset by the high quality of the country’s mineral deposits, the likely outcome for the foreseeable future is business as usual.

The lack of depth in the financial sector is a perpetual headwind to the country’s sustainable and diversified growth. The DRC, a nation that spans the equivalent of two thirds of Western Europe, has less than 20 licensed banks, lacks a domestic stock exchange and, with a mere US$5 billion in aggregate bank assets, could not fund a major mining operation. “Although it is improving, the sources of funding in the country are scarce and highly volatile,” said Olivier Duterme, regional director at Banque Commercial du Congo (BCDC). “At this stage, it is still difficult for us to provide long-term credit to clients, which is a necessity for the economy to grow.”

The lack of credit capacity is partly linked to the country’s tattered road and power infrastructure that makes opening a bank a costly affair. Without ATMs, local branch offices and cash delivery – all dependent on reliable road and power access – the number of bank account holders is unlikely to climb considerably higher than the current 7% of the population. To increase the domestic bank capacity, the DRC needs more international investment as well as greater popular participation in the banking sector. However, investments over the last years have been scarce, and from a mining perspective, as pointed out by Gaëtan Munkeni, regional director of First Bank Nigeria (FBN): “The growth you see at production level is contributed by the same players that have been in the market for years […].”

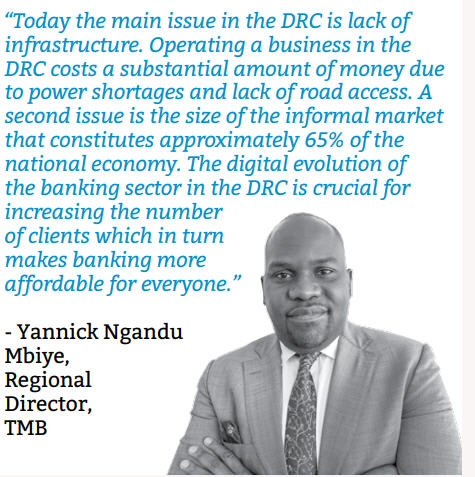

“The overall growth is further undermined by the size of the informal market that constitutes approximately 65% of the national economy,” added Yannick Ngandu, regional director of TMB. The result of the weak banking system is higher national banking costs as payments in U.S. dollars are done through American banks for a commission. Accordingly, much of the overall urban economy uses U.S. dollars as its default currency, which brings exorbitant costs for withdrawals.

With bank assets to GDP sitting at 7% – one of the lowest numbers in the world – domestic banks are forced to think outside the box and look beyond the corporate sector to grow their capacity, which is why BCDC and FBN alike have turned their eyes to the country’s growing retail sector. “Retail banking is something quite new in the DRC, as banks only started to develop a strategic approach to retail clients in 2011,” Duterme said. “Today, we have a significant foothold in the retail sector that does not only encompass individuals but small to mid-size companies as well.”

Despite the majority of the DRC’s population still living below the poverty line, the increase in ATM usage since the first installation a little over a decade ago is a testament to the population’s growing purchasing power. According to the World Bank, the DRC had 0.1 ATMs per 100,000 adults in 2009, which increased to 1.31 ATMs per 100,000 adults in 2015.

Munkeni elaborated on FBN’s strategy to serve the retail market, stating: “We need to increase our transactional banking and microloan volumes. The banking industry is moving towards the digitization of transactions, which includes cards, ATM’s, mobile banking apps, internet banking and various loan products designed for specific sectors of the retail market such as students, workers etc.”

In the last few years, internet banking has caught up with the DRC’s telecommunication boom, which is likely to keep accelerating after the government’s decision in 2018 to grant 4G licenses. While the country’s telecom penetration remains low even by African standards, the DRC’s 79 million inhabitants hold 48 million SIM cards, according to the mobile operator association GSMA, which leaves plenty of room for operators to follow the entry of major players like Orange and Vodacom. Thus, mobile banking, which has steadily grown since the government’s decision in late 2011 to pay civil servants through banks, will help to overcome problems of poor infrastructure and a dual currency regime by extending saving and payment alternatives to rural and urban-peripheral areas. Domestic banks across the board are investing in mobile platforms, such as TMB’s Pepele Mobile that was launched in 2015 and has since become one of the most popular banking tools in the country available on all platforms and in five languages. “The service is powered by cutting-edge, fully secure technology, and customers can complete a range of banking activities such as withdrawing cash, making deposits and transferring funds, as well as making payments in shops, restaurants and other commercial establishments,” Ngandu said.

However, while digitalization of the economy will pave the way for improved personal savings and increased credit access in the long term, mining companies will, for the foreseeable future, have to look to overseas funding options such as raising capital on foreign exchanges with strong connections to Africa. “The London Stock Exchange has more than 110 African companies listed in London representing a US$200 billion total market capitalisation,” said Tom Attenborough, head of international business development primary markets at London Stock Exchange. “In terms of market cap, this puts us second only to Johannesburg in terms of African securities.”

Some companies turn to private equity firms such as London-based Tembo Capital Management, which focuses on supporting junior and mid-tier mining companies in emerging markets. “Tembo is a private equity mining firm with a 10-year tenure, with a potential two-year extension, which allows us to hold investments for a longer period,” said Tembo principal Peter Ruxton.

While most short-term investors such as unit trusts or pension funds prefer to be involved in a selected part of a project’s development cycle, typically looking for investment returns of 8-10% per annum plus, Tembo aims to make multiple times its initial investment over a three to five-year period or longer. “We support companies from as early as the initial pre-production stage, including pre-feasibility studies, basic engineering and geological work, to construction of a cash-generating mining project,” he continued.

Another available finance option is to turn to banks with backing from larger international groups. “After reconsideration, we decided to pull out of personal banking less than a year ago, closing the Goma and Matadi branches, and giving our full attention to corporate clients, which are primarily MNCs and their core value chain,” said Serge Bilambo, head of mining and metals at Standard Bank DRC.

As part of the larger Standard Bank Group, the bank is able to support larger investments for clients in individual countries. “From a regulatory perspective, we have to consider the single obligor limit which is the maximum that we, as a legal entity, are permitted to credit to any single customer,” Bilambo said. “This is limiting the capacity of banks in the DRC to fund larger investments, but as part of Standard Bank Group, we can lend much higher sums with a risk participation from the Group.”

Thus, funding options are available for quality projects in the DRC, but the high-risk environment brings a selectivity to foreign investors, which undermines chances of additional tier-one discoveries as well as the necessary diversification of the economy. Provincial governments are tackling the issue by pushing for alternative investment opportunities in their respective regions, with agriculture and tourism earmarked as the key sectors in the Copperbelt region. The cost of eggs, milk and chicken in urban areas of the DRC is almost double that of neighboring countries. Bringing down retail prices by investing in agriculture will considerably ramp up consumption and spread risk to areas outside of mining. In addition, the liberalization of the formerly state-controlled insurance sector in 2017 could work to slash interest rates for domestic loans and strengthen the national market.

On the corporate side, domestic banks have discussed a collaborative approach to increase credit capacity. “If the economy and corporate banking sector continues to grow at the current pace, we will have to collaborate to satisfy market needs,” said Munkeni.

This sentiment was echoed by Duterme: “The banking sector should increase collaboration to better their capacity for funding major projects. Some banks are active with financing programs with international banks, but there is still a significant amount of room for improvement.”

(By Carl-Johan Karlsson)

(This story first appeared in Global Business Reports)

Comments