Uranium industry weighs rules that have bomb watchers twitching

Back in the 1970s and 1980s when he was keeping America’s nuclear weapons up to date, Robert Kelley didn’t pay much attention to their source of uranium.

But then he was reassigned to lead the international team that accounted for the of hundreds of tons of the heavy metal Iraq secretly extracted at a fertilizer factory to feed Saddam Hussein’s weapons program.

That discovery at the Al-Qaim phosphate plant underscored a loophole in the global policing of nuclear materials, allowing countries without much scrutiny to derive uranium from a mineral more often used as a nutrient for soil. It’s also why Kelley and his colleagues are now concerned that United Nations officials and atomic regulators are poised to loosen rules on the industry, unlocking finance to take more radioactive material out of the ground without corresponding new checks.

While the change could potentially cut mining waste, it might also lead to a reduction of the scrutiny uneconomical projects get from nuclear inspectors

“Uranium extraction from phosphates flies under the radar,” said Kelley who also inspected phosphate plants in Egypt and Syria as a director with the International Atomic Energy Agency. “This isn’t a theoretical risk. It’s real.”

Diplomats at the UN and IAEA have proposed reclassifying uranium as a “critical material.” That would allow countries to tap funding from the World Bank and other development institutions to ensure supply under the guise of the UN’s sustainable development goals. While the change could potentially cut mining waste, it might also lead to a reduction of the scrutiny uneconomical projects get from nuclear inspectors.

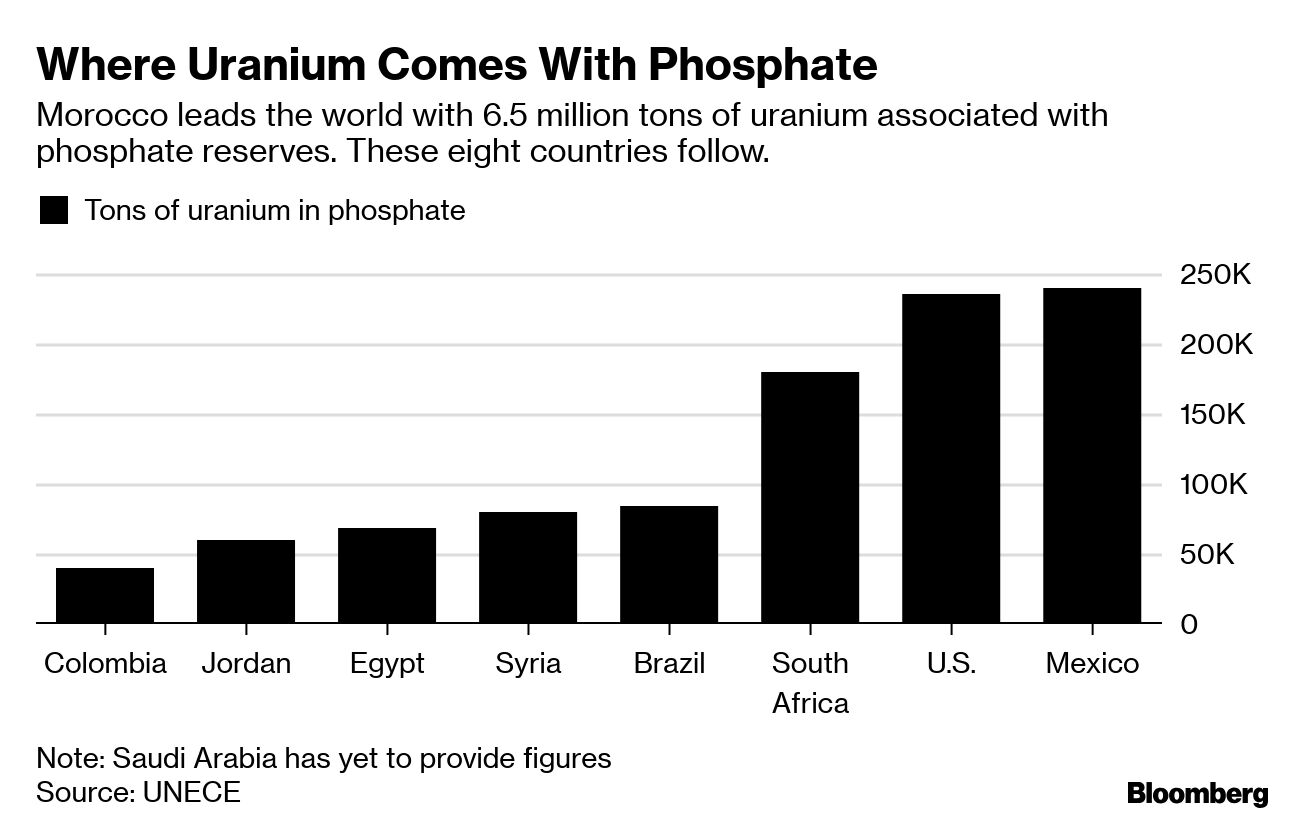

The biggest beneficiaries to the new rules would be countries including Jordan and Saudi Arabia, which have large reserves of phosphate and growing populations that need to be fed with the crops it fertilizes. However the extraction process could weigh on the uranium market, where prices have stagnated since the last recession started in 2008.

“The main use of phosphate is in fertilizer, but it can also contain a lot of uranium,” said Harikrishnan Tulsidas, a UN official and former IAEA mining adviser who was one of the proposal’s authors. By turning uranium into a byproduct of phosphate, the nuclear industry could blunt “boom-bust” mining cycles by linking uranium supply with other industries, like agriculture, he said.

Strong links between phosphate and uranium emerged as far back as the 1950s in the U.S., according to a Stockholm International Peace Research Institute report co-authored by Vitaly Fedchenko. America’s earliest nuclear arsenal used uranium derived from a fertilizer plant in Florida. Countries from Israel, India and Pakistan have also looked to phosphate as a way around import restrictions for atomic material, according to Kelley, who called the method “a sore on the non-proliferation landscape.” His assessment of the site in Syria was triggered by concerns of John Bolton, who is now the national security adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump.

To derive uranium, phosphate rocks are ground and milled at the plants before being fed into a chemical process yielding phosphoric acid. Another stage of chemical treatments yields a black uranium concentrate that can appear in powdery or sludge-like form, according to Kelley, who now advises governments from a Swedish security institute.

Though in its elemental form uranium can’t fuel a reactor or make a bomb – it first must be enriched or turned into plutonium — it’s the fundamental ingredient for all nuclear programs. BHP Group Ltd.’s Olympic Dam is currently the world’s biggest uranium mine. Morocco’s OCP SA sits on the largest quantity of the heavy metal, buried in the kingdom’s vast phosphate reserves.

One of the countries pursuing recovery of phosphates and uranium is Saudi Arabia. Energy Minister Khalid Al-Falih said a year ago that the kingdom possesses “significant uranium reserves” that it intends to tap, but which haven’t been accounted for by international monitors. Saudi Arabia also has plans to mine phosphates, which it estimates could be as high as 7 percent of the world’s reserves.

Saudi government officials had no comment. The state-backed producer, Saudi Arabian Mining Co., brushed aside the idea that the kingdom’s phosphate could be a major producer of uranium.

“Our phosphate has very low uranium content, so it wouldn’t be the obvious source,” Darren Davis, the chief executive officer of the company known as Maaden, said in an interview. “Whether it’s feasible or not, I think the technology as well is not well proven. There’s more work to be done on that.”

The kingdom is pursuing nuclear power but has also has warned it could seek weapons too. Saudi Arabia is unique among countries with the potential to extract uranium from phosphate: it’s flush with oil money to invest and has signaled an ambition to build a nuclear program.

The technology needs big financial backing. Commercial plants cost as much as $1.3 billion, according to Julian Hilton, who advocates for “green nuclear fuel sources” and helped draft the UN’s new guidelines.

“This is at the center of the food, energy and water triangle that’s the key to everything,” Hilton said in an interview. Phosphate extraction is a “win-win for everybody,” resulting in cleaner fertilizer, at reduced energy intensity, with uranium collected as a valuable byproduct, he said.

The risk that uranium is diverted for weapons could be reduced if countries adopted stricter international rules to safeguard uranium stockpiles. But implementing tougher rules, what the IAEA calls an additional protocol, aren’t required as a precondition to get aid in recovering uranium from phosphate, according to IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano.

That’s a concern among non-proliferation experts because of the IAEA’s checkered past with uranium. The agency helped Pakistan develop resources that likely went into that country’s weapons program. In Syria, under investigation since 2007 over clandestine nuclear work, the IAEA helped build a pilot extraction facility at a fertilizer plant in the city of Homs.

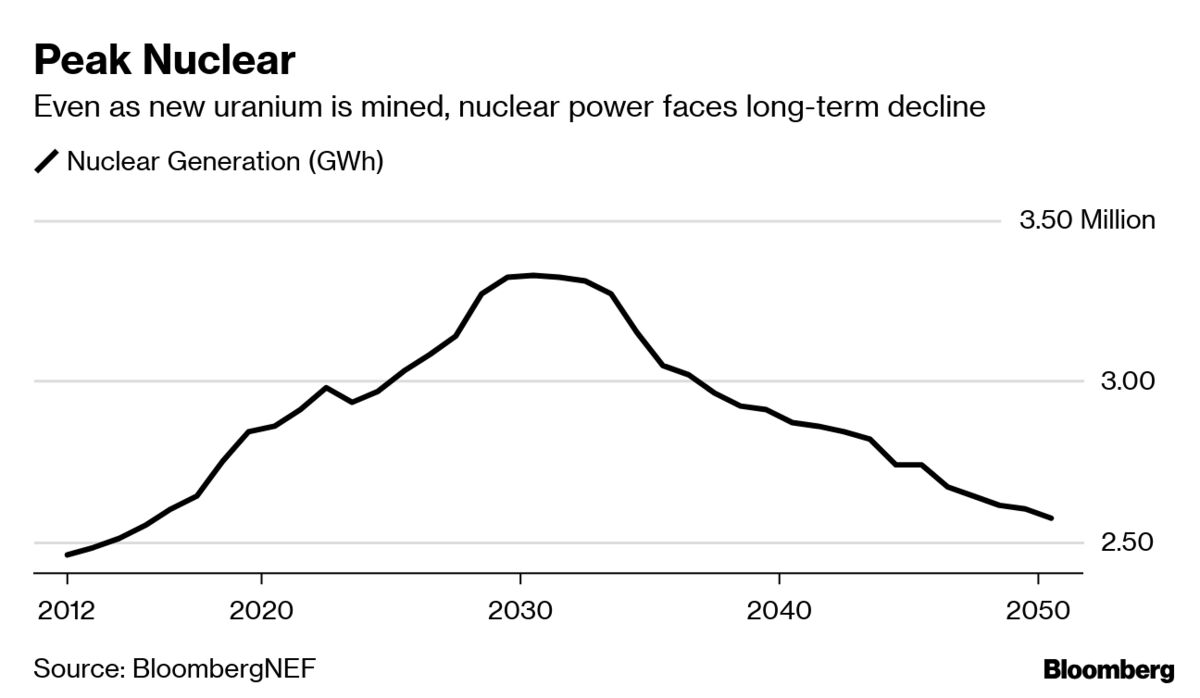

Over the last decade, the market for reactor fuel has been battered by safety concerns, cheap natural gas and the shift toward decentralized electricity grids powered by renewables

“Doing it with the IAEA and UN gives a kind of cover that allows countries to take one small step without raising suspicions,” said Scott Kemp, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who advises the U.S. government on non-proliferation. “If this technology is used, it begs the question what will be done with the material?”

Based on current prices, it’s cheaper for countries that want nuclear power to buy uranium on the market than it is to invest in new exaction. Over the last decade, the market for reactor fuel has been battered by safety concerns, cheap natural gas and the shift toward decentralized electricity grids powered by renewables.

“Recovering uranium from phosphate is not economic at the moment,” said Nick Carter, a vice president at UX Consulting Co, which advises makers of nuclear fuel. Prices would have to rise three-fifths just to break even, he said.

Farm demand for uranium-free phosphate fertilizers is also slack, according to Alexis Maxwell, research director of Green Markets, a fertilizer research firm owned by Bloomberg LP. The Houston-based analyst said that adopting uranium extraction would “pose risks to fertilizer companies.”

With the UN set to issue its final uranium-resource guidelines later this year, the weapons-investigator Kelley said international monitors should pay attention to those market signals.

“Because this process isn’t economically competitive, the IAEA should be especially cautious when assisting countries to produce uranium.” Kelley said. “It means they’re acquiring uranium for other purposes than power and that should raise a flag.”

(By Jonathan Tirone)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments