When Arab members of Opec resolved to cut their oil exports in response to U.S. involvement in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, the situation was rightly deemed a global crisis.

Less than a year after BHP Billiton Ltd. announced plans to merge its iron ore operations with those of Rio Tinto Group in 2009, the proposal was dropped amid expectations that regulators in Europe and Asia would oppose the deal on antitrust grounds.

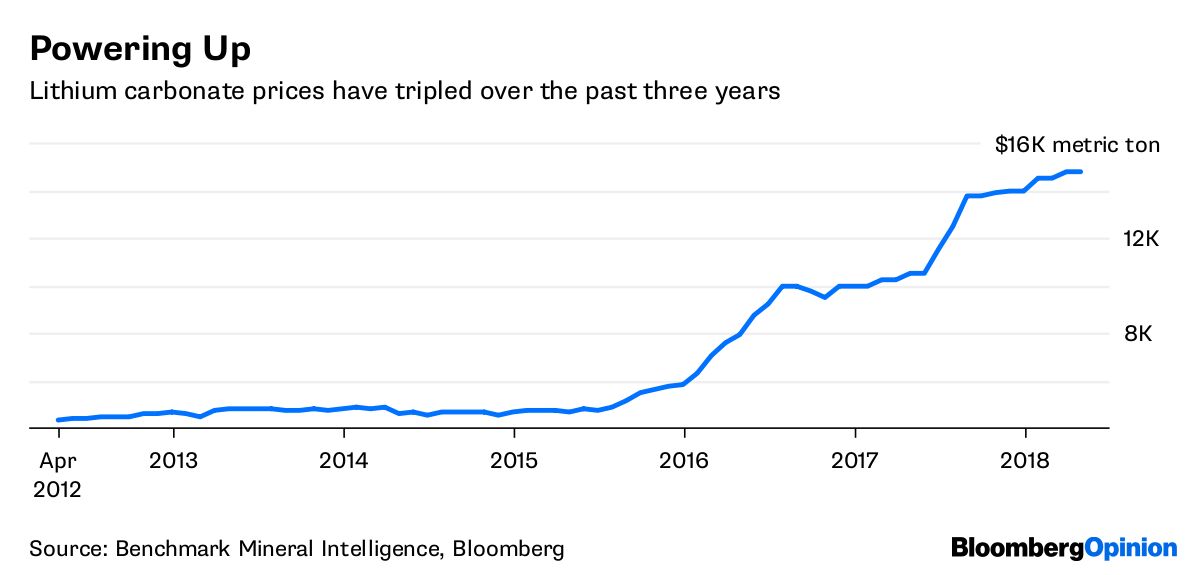

So why is there so little noise about the emerging oligopoly in one of the hottest elements on the periodic table, lithium?

Tianqi Lithium Corp. will pay $4.1 billion to buy Nutrien Ltd.’s 24 percent stake in Soc. Quimica & Minera de Chile SA, or SQM, in a deal that will entangle the biggest and fourth-biggest producers of the battery metal. The transaction could theoretically give Tianqi half of the board seats, though other major shareholders who’ve historically guarded their interests have opposed such a path.

The transaction could theoretically give Tianqi half of the board seats, though other major shareholders who’ve historically guarded their interests have opposed such a path.

Here’s how the lithium carbonate market is structured at present: North Carolina-based Albemarle Corp. is the market leader, with an 18 percent share, followed by Jiangxi Ganfeng Lithium Co. on 17 percent; SQM on 14 percent; and Tianqi on 12 percent. Other players have the 39 percent or so that remains – the largest among them being FMC Corp., which is soon to offer its shares to whoever wants them in a planned initial public offering.

That in some ways understates how connected these players are. The single biggest mine deposit is a joint venture between Albemarle and Tianqi, the Greenbushes mine in Australia, which alone accounted for about 35 percent of global lithium carbonate-equivalent supply last year. Albemarle’s other major deposit is the Atacama brine lake, adjacent to SQM’s deposits in Chile.

On top of that, Ganfeng and Tianqi, while both technically independent private companies, are strategically important businesses operating in the China of 2018. Tianqi Chairman Jiang Weiping is a delegate to China’s National People’s Congress, according to the company’s latest annual report. Ganfeng Chairman Li Liangbin has been a member of the standing committee to the People’s Congress in Xinyu city, where the company is based, according to its IPO prospectus.

It’s hard to imagine that these companies could remain wholly immune to influence from Beijing, at a time when China is trying to make itself the center of the global electric-vehicle industry amid international trade tensions.

To be sure, the shape of the market will change dramatically, with lithium carbonate output set to rise from 228,000 metric tons in 2017 to 574,000 tons in 2022. But because of the high margins enjoyed by incumbents at current prices and their ambitious capacity-expansion programs, the biggest producers are likely to capture the majority of supply growth over the years ahead, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Christopher Perella.

The outlines of the oligopoly are also indistinct. Tianqi is only a minority shareholder in SQM; it’s only connected to Albemarle through a joint venture that accounts for a bit less than half of Albemarle’s output; and Beijing has no formal control over private Chinese companies, whether they’re Tianqi or Ganfeng.

Still, the world’s regulators should sit up and take notice of what’s happening. Those who’ve fretted in recent years over Beijing’s dominance of rare earths and tungsten – not to mention the current tariffs on steel and aluminum justified on national defense grounds – seem to be asleep at the wheel.

If your hopes for a free market in lithium depend on the outcome of board tussles in Santiago, joint-venture decisions in North Carolina, and Chinese executives’ willingness to buck pressure from Beijing, they’re thin indeed.

(By David Fickling)

Comments