South Africa’s golden age is dead. Good riddance — opinion

Even the richest mine eventually runs out.

That’s what’s happening in South Africa, where AngloGold Ashanti Ltd. announced plans Thursday to dispose of its last remaining pit in the country, just as voters were heading to the polls for the sixth general election since the end of apartheid.

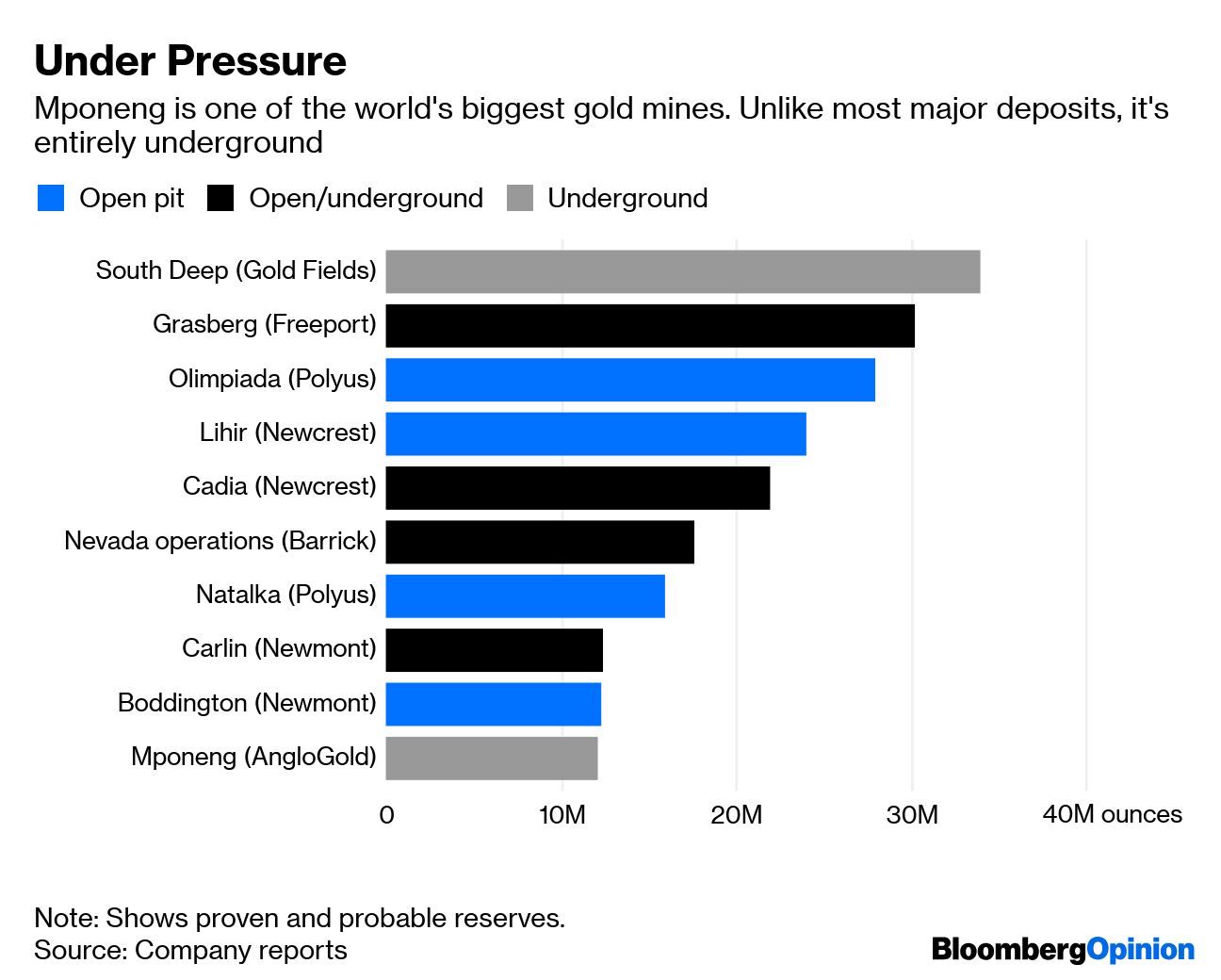

A transaction for the Mponeng mine southwest of the capital Johannesburg is unlikely to rock financial markets or cause a great political upset. While it’s still one of the world’s 10 biggest gold reserves, AngloGold will do well to get more for the pit than its $533 million carrying value at the end of 2018.

Even so, a sale (and the shift of AngloGold’s main listing to London or Toronto that would probably follow) would mark a turning point for the country

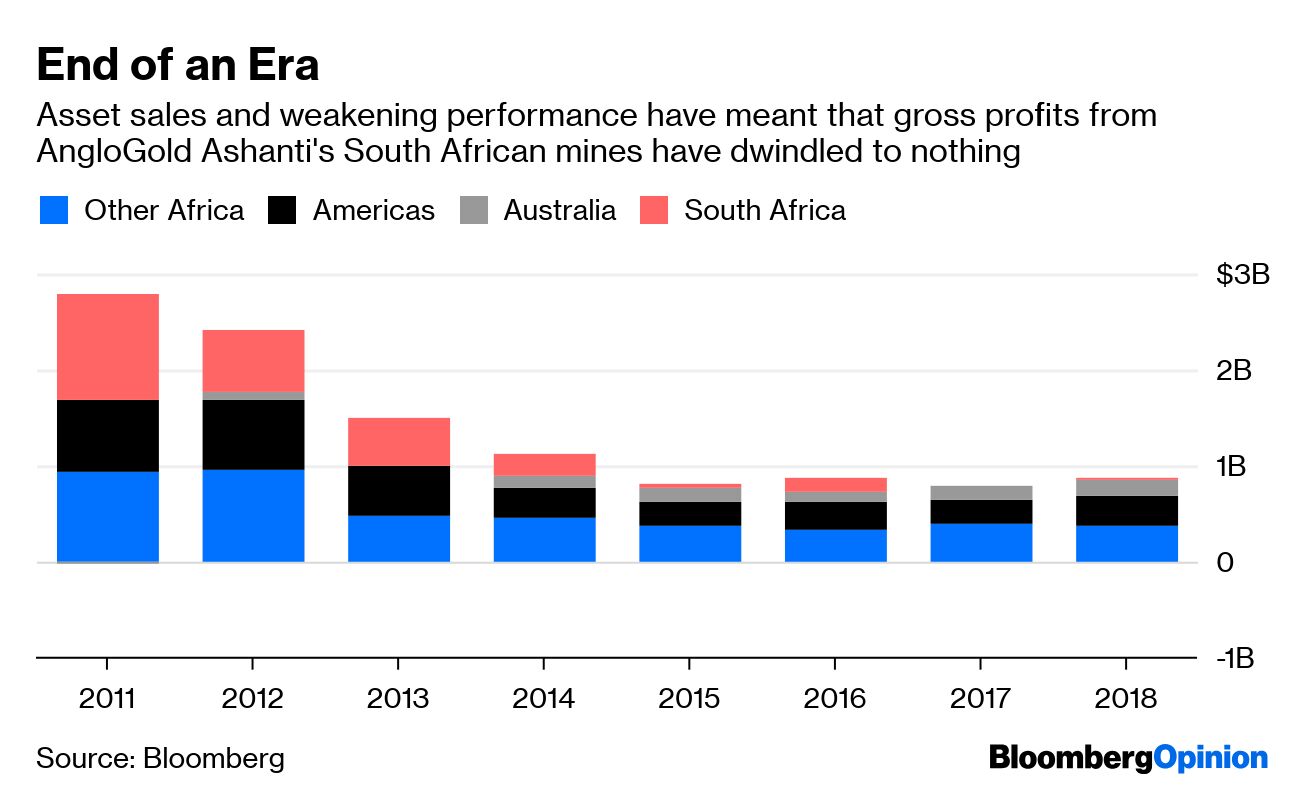

Even so, a sale (and the shift of AngloGold’s main listing to London or Toronto that would probably follow) would mark a turning point for the country. As Felix Njini of Bloomberg News has detailed in multiple articles, the gold mining industry that built South Africa and produced about half of the yellow metal that’s ever been dug up seems now to be in terminal decline.

Despite ore containing almost 10 grams of gold per metric ton – an extraordinarily rich grade in an industry where levels one-tenth of that are considered decent – the challenges of making money at Mponeng are immense. It’s the world’s deepest mine and the commute two miles down from the surface takes an hour, with ice and concrete pumped down to cool and stabilize the hot, under-pressure rocks. In common with other South African gold pits like Sibanye Gold Ltd.’s Driefontein and Gold Fields Ltd.’s South Deep – both potential buyers of Mponeng, along with Harmony Gold Mining Co. – it’s on its last legs despite an illustrious history and theoretically rich reserves.

AngloGold and the Witwatersrand deposits these mines exploit are deeply bound up with the history of South Africa. It was a late 19th century gold rush that led to the founding of Johannesburg. Gold formed the original core of AngloGold’s one-time parent Anglo American Plc, a conglomerate that at one time reached into so many corners of South Africa’s life that it was likened to an octopus. While Anglo American’s founding Oppenheimer family and their successors were vocal opponents of apartheid, their empire was still built on the cheap black labor generated by that system.

No pay agreement or restructuring is likely to change the fact that comparative advantage in the global gold market lies with giant, lower-grade pits in Siberia, Nevada and the Pacific rim

Labor is still a decisive issue in South Africa’s gold mines. Workers last went on strike at Mponeng in 2012, but industrial action is a constant threat; courts blocked another attempted action in 2014. South Deep and Driefontein have both been crippled by strikes over the past year, and the latter is now being gradually closed down.

These fractious workplace relationships aren’t so much the fault of refractory unions or exploitative bosses, as the inevitable outcome of poor geology. In most parts of the world, the biggest gold reserves are contained in open pits that can be dug from the surface with explosives, dragline excavators and 400-ton dump trucks – or at the very least, in underground mines that are developed only as a last resort when the surface pit is exhausted.

In South Africa the biggest mines are entirely underground, where workers must drill the walls of sweltering tunnels to extract the ore lump by lump. That contributes to accident and fatality rates well above the industry average, as well as strikingly poor productivity. Harmony Gold uses almost three times as many employees as Newmont Goldcorp Corp. to produce just one-fifth of its revenue. South Deep is arguably the richest gold deposit in the world, with 34 million troy ounces of contained metal, but Gold Fields loses several hundred dollars on every ounce it digs up.

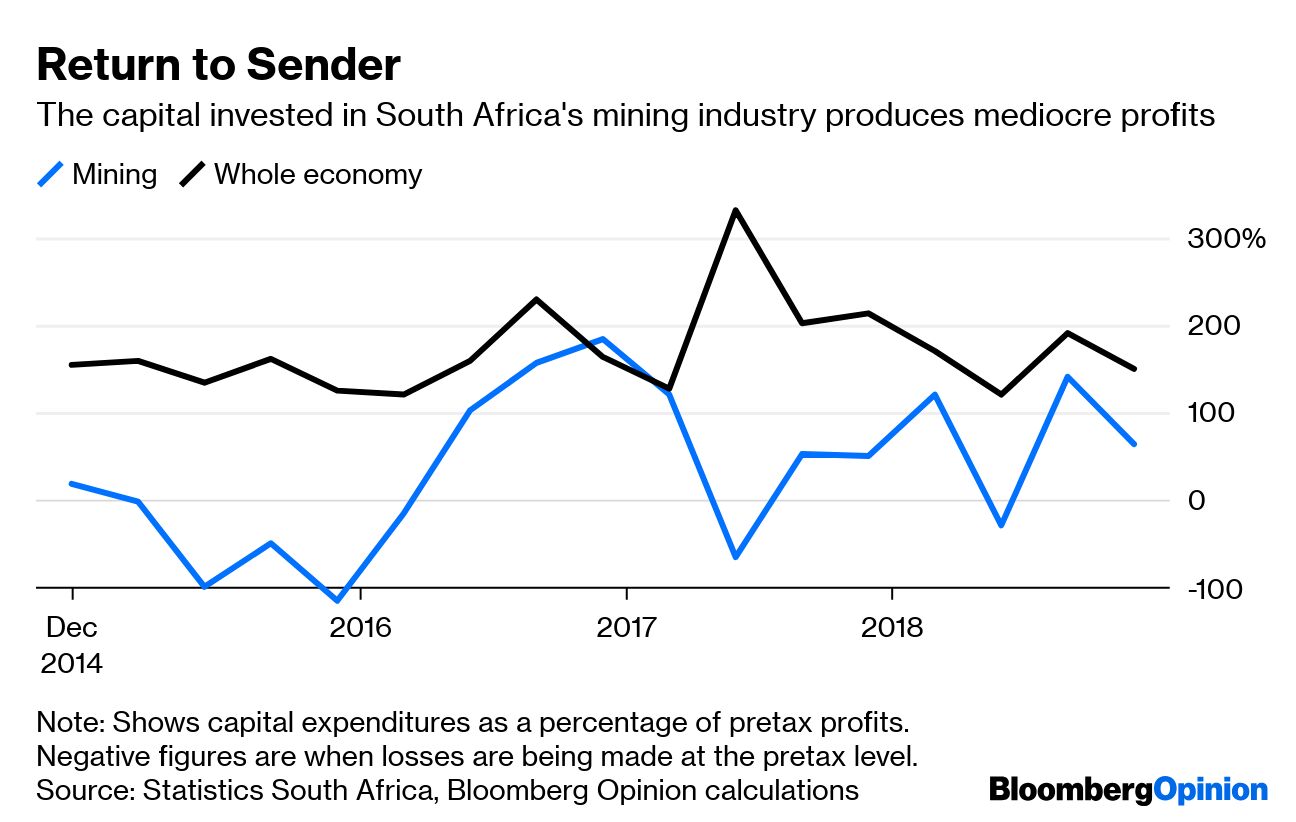

No pay agreement or restructuring is likely to change the fact that comparative advantage in the global gold market lies with giant, lower-grade pits in Siberia, Nevada and the Pacific rim. As a result, labor and capital in South Africa are tussling over a profit pie that’s simply too small to feed them both adequately.

It’s tempting to see echoes of South Africa’s recent economic stagnation in the slow death of its century-long gold rush – but the country shouldn’t shed many tears over the decline of this dangerous, unprofitable business.

President Cyril Ramaphosa looks to have a strengthened mandate to pursue economic reforms after the May 8 election. The onetime mine union leader and director of platinum producer Lonmin Plc will need to push South Africa down a less resource-intensive road if he’s to pull the country out of its economic funk. Pretax income from the mining industry only fitfully rises above its level of capital expenditure, a sign that funds could be better deployed elsewhere.

If the confidence of consumers, domestic businesses and foreign investors is to revive, it will need to focus more on the 93 percent of the economy that doesn’t involve digging rocks out of the ground. South Africa’s golden age is dead. Its people shouldn’t mourn that fact.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments