Copper faces double supply disruption threat in 2018: Andy Home

LONDON, Jan 10 (Reuters) – One down, plenty more to go.

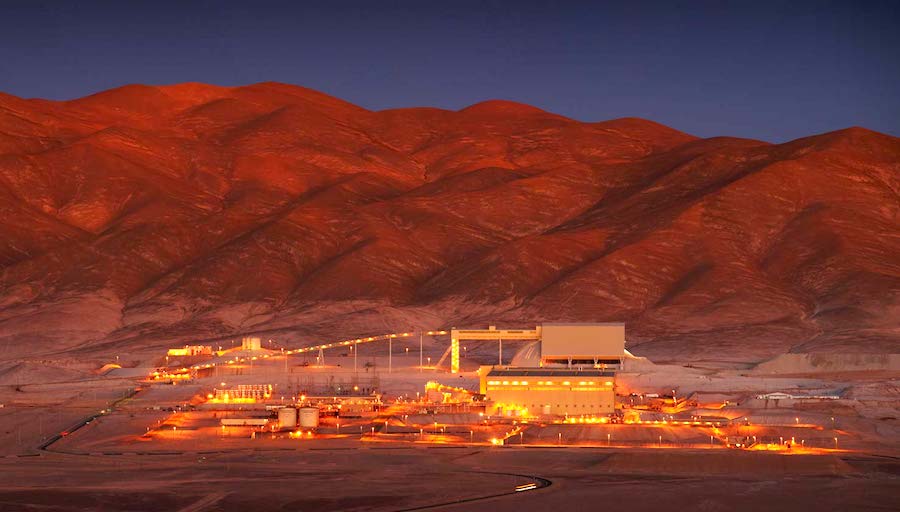

The Lomas Bayas copper mine in Chile, operated by Glencore, has just averted a threatened strike. Unionised workers accepted the terms of a new labour contract at the eleventh hour.

The number of labour contracts up for renewal this year, most of them in Chile and Peru, is the highest since 2010.

The threat to mine supply from strike action looms large, not least at the world’s biggest coppermine, Escondida, where a 44-day walkout last year ended with no meeting of management and union minds.

Analysts have collectively tweaked their supply disruption allowances to factor in the potential for labour unrest this year.

However, copper faces a double disruption threat in 2018. The second comes from the shadows of the copper scrap sector, an important but statistically opaque part of the supply chain.

China’s clampdown on imports of low-grade scrap, “foreign garbage”, has already sent tremors through the plastic and paper sectors.

Now, it looks as if it’s copper‘s turn. A new raft of measures, if fully enacted, risks stemming the flow of scrap to the world’s largest volume importer.

To quote Michael Lion, president of Lion Consulting Asia and a seasoned veteran of the scrap trade, “at the very best, there is going to be an enormous dislocation and disruption in the coppersupply chain.”

Changing the rules

An announced tweak to China’s copper scrap import regulations jolted the market into life last July.

The threat at that time was that imports of “Category 7” scrap would be banned at the end of 2018.

Which seems to remain the case.

“Category 7” scrap, comprising products such as cables and motors which need to be physically dismantled and sorted before being processed, remains on the 2018 list under the “restricted” column.

Chinese operators have lost no time in offshoring the processing of this type of material to other Asian countries in preparation for a full halt in imports.

This is low-grade stuff, typically containing about 14-15 percent copper, and accounts for only a relatively small part of China’s total copper import needs.

Much more significant are two other policy changes, both of which should be seen in the context of Beijing’s “clear skies” policy of slashing pollution levels.

The first is the systematic elimination of the middle man in China’s copper scrap supply chain.

The Ministry of Environmental Production announced on Dec. 15 that only end-users and processors of copper scrap would be allowed import quotas this year. Traders and merchants, apparently, need not apply.

The second is a proposal from March to limit hazardous impurity levels to 1 percent, a quality threshold only the purest copper scrap can be expected to pass.

The cumulative impact of these two rule changes has been a near collapse in applications for new 2018 copper scrap import licences.

Graphic on China’s copper scrap imports 2003-2017

Three million and counting

China imports more than 3 million tonnes of copper scrap, bulk weight, every year.

Inbound flows fell steadily over 2013-2016, partly because of earlier quality control measures by the Chinese authorities and partly because the copper price was bombed out.

At low prices the supply of old scrap dries up, acting as a counterbalance to excess supply in the primary part of the market. When the price recovers, the scrap chain bursts back into life again.

This is what has happened in the copper market over the last year or so. A sharp recovery in price over the course of 2016-2017 has seen scrap supply surge with price discounts widening and China soaking up the extra units.

Last year’s cumulative imports through November were up 9 percent, the first year-on-year rise since 2012.

Next year, however, could be a very different story, unless the authorities relent on the new import restrictions.

If they don’t, a significant supply hit for copper in the form of scrap will translate into greater appetite for copper in other forms, either refined metal or concentrates.

Imports of refined copper were down 11 percent in the first 11 months of 2017 but November’s count of 329,000 tonnes was the highest since December 2016 and an upside surprise.

Is it a taste of things to come? The next few months’ trade figures will bear close scrutiny.

Graphic on U.S. copper scrap prices

“Dislocation and disruption”

If China faces a copper scrap famine, the rest of the world faces a feast.

Scrap price discounts continue to widen in the United States.

That for “No. 2” scrap, typically wire and pipe that needs to be cleaned before processing, is assessed at 41 cents/lb below CME cash copper by S&P Global Platts. It has flexed wider from 30 cents/lb in July.

“No. 1 bare bright” scrap, the purest grade, is trading at a 14-cent discount, compared with an 8-cent discount a year ago.

It is possible that COMEX copper‘s late-2017 surge through the $3.00/lb level has generated a second wave of old material.

But it is also possible we’re seeing the first signs of back-up from this year’s revised Chinese import regime.

The global copper scrap supply chain seems to be facing a period of maximum “dislocation and disruption”.

China will be short of scrap while the rest of the world sees supply steadily increase.

Over the longer term, market flows should readjust.

The ongoing offshoring of the dirtier “Category 7” Chinese scrap sector could herald a far bigger migration for other types of material.

China’s own scrap generation and processing chain will steadily grow and become more organised.

Both processes are going to take time.

Beijing, however, seems to be in a hurry.

China’s metals scrap sector is now firmly in the authorities’ sights. It will be “cleaned up”, literally and metaphorically.

As of the end of November, 259 people had been arrested for smuggling “foreign garbage”. The ports of Xiamen and Qingdao have both seized cargoes of banned zinc waste over the last two months. The customary waves of official inspections are being rolled out.

Beijing has already shown its willingness to accept short-term disruption to whole manufacturing sectors in its “clean skies” campaign.

The waste paper sector, where import controls have seen Chinese prices soar and supplier stocks build, may offer a glimpse of what might happen to the copper market.

This coming upheaval in the scrap part of the supply chain is going to be a lot less visible than the calendar of expiring mine labour contracts.

But its impact, both on price and industry structure, could be more far-reaching.

(Column by Andy Home; editing by Dale Hudson)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments