Copper benchmark deal signals shifting supply dynamics in 2019: Andy Home

Copper supply has surprised this year, but not in the way everyone expected.

It was supposed to be a year of mine disruptions, with the market anticipating that multiple labour contract expiries would result in at least one strike, and possibly more.

In the event there was none.

By copper’s standards it has been a remarkably smooth year for mine production, leaving analysts struggling to fill the customary collective allowance for disruption in their forecasts.

There has been plenty of disruption, but it has taken place at the smelting-refining stage of the copper production chain, roiling the refined metal market and allowing smelters to feast on a rare abundance of raw materials.

This dynamic looks set to change again next year, judging by the benchmark copper concentrate terms set by Chilean miner Antofagasta and China’s Jiangxi Copper.

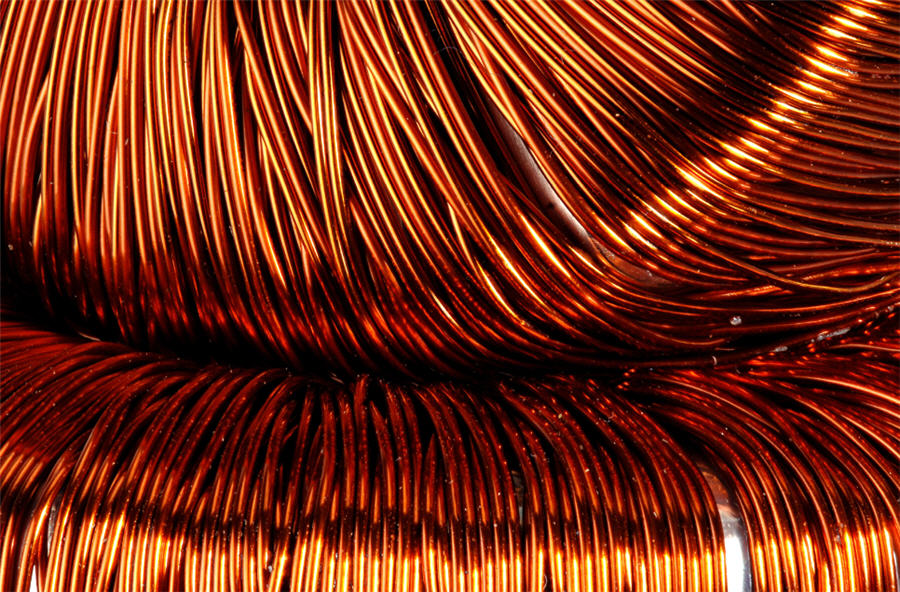

Graphic on copper concentrates benchmark terms 2006-2019:

Fraying benchmark

The headline deal between the two companies for 2019 is for Jiangxi to receive a treatment charge (TC) of $80.80 per tonne and a refining charge (RC) of 8.08 cents per pound for converting Antofagasta’s concentrate into refined metal.

That is down from this year’s benchmark terms of $82.25 and 8.25 cents and marks the fourth consecutive year of falling treatment charges.

Whether they are really “benchmark” terms is questionable since the whole annual benchmark system for pricing copper raw material is evolving.

BHP Group, which used to take the lead in negotiating the benchmark, has been steadily shifting its pricing strategy towards shorter-dated and spot contracts.

Freeport McMoRan, which has assumed the miners’ benchmark-setting role in the last couple of years, is going to have much less material available for sale next year as its Grasberg mine in Indonesia starts transitioning from open-pit to underground mining.

Step forward Antofagasta to lead the miners this time around.

The company may be a reluctant benchmark setter though. To quote analysts at BMO Capital Markets, Antofagasta has in the past “been able to cut special deals at low TCRC terms for (its) Los Pelambres concentrate, which produces the highest grade among major Chilean mines”. (“Copper: It’s TCRC Time Again”, Nov. 9, 2018).

There is always much latitude in how miners and smelters price off the annual benchmark, reflecting the wide spectrum of concentrates quality and levels of impurity, and this year may well see a wider than usual array of contract terms.

However, for want of anything else, Antofagasta and Jiangxi’s deal is the 2019 benchmark and one that points to significant shifts in the copper supply picture.

Mine supply slows

The first shift will be a sharp slowdown in growth in mined production.

Global mined copper production rose by around 3 percent in the first eight months of this year, according to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG).

It looks on track to meet comfortably the ICSG’s forecast of 2 percent growth over the whole of 2018.

That doesn’t sound like much but it’s a marked improvement from 2017, when the ICSG estimates global mine production fell by 1.5 percent.

The relative abundance of mined concentrates this year has been evident by the accelerated flow of material into China, the world’s largest single smelter-refining processing hub.

Imports of concentrates surged by almost 20 percent to 16.6 million tonnes in January-October, marking a record pace of import.

The feast is not going to last.

The feast is not going to last.

Mine supply is forecast by the ICSG to slow to 1.2 percent next year. The wave of new mines and expansions that started in 2015 and 2016 is now levelling off.

BMO, which forecasts a similar rate of growth, notes that “while there are plenty of larger operations coming during 2022-2023, for 2019 only First Quantum’s Cobre Panama operation is adding in excess of 100,000 tonnes to the market”.

Meanwhile, lower production at Grasberg, one of the world’s largest mines, is now a “known known” after Freeport’s third-quarter guidance that output would drop to around 250,000 tonnes from this year’s expected 525,000 tonnes.

Unexpected mine disruption is always the “known unknown” in the copper market and it seems unlikely 2019 will prove as smooth as this year has turned out to be.

More smelter capacity

The unexpected twist in copper supply this year has been the level of disruption at the smelting-refining stage of the supply chain.

The closure in April of Vedanta Resources’ 400,000-tonne per year Tuticorin plant in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu was wholly unforeseen.

It has flipped India from being a net exporter of refined copper to a net importer, drastically reshaping physical copper flows.

So far at least there is no sign of the state government going back on its closure order.

Glencore’s Pasar smelter in the Philippines should return to normal operations after extensive work to repair damage caused by a typhoon at the start of the year.

But Chilean state producer Codelco has flagged potential problems with upgrades of its smelters to meet new environmental standards.

Overriding this ongoing disruption, however, is the expected commissioning of more refining capacity in China, led by Chinalco’s new 400,000 tonnes per year plant.

It will be the first of a new generation of “large, environmentally efficient and technologically advanced” plants due to enter production over the next three years, according to BMO.

It will be the first of a new generation of “large, environmentally efficient and technologically advanced” plants due to enter production over the next three years.

Given restricted growth in the amount of concentrates available next year, these new smelters will have to compete for raw material.

The drop in the 2019 benchmark treatment terms is largely down to Chinese smelters accepting the resulting hit on their negotiating power.

All change again

These copper concentrate benchmark deals say more about the state of supply and demand in the raw materials’ segment of the supply chain than they do about the refined metal balance.

However, copper’s fundamental outlook is always beholden to how much comes out of the ground. This year has turned out to be a rare exception to that rule.

From that perspective, the 2019 benchmark is signalling both that mine supply is going to drop a gear again and that new Chinese capacity will mitigate against the smelter bottleneck that has defined the physical market this year.

But as ever with copper supply, it is next year’s “unknown unknowns” that will determine outright copper price levels.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Susan Fenton)

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments