Coal’s collapse crowns winners and losers from China to the US

It’s been a stormy month for benchmark coal prices in Asia, with the potential for reverberations across the globe.

A double whammy of Chinese import curbs and collapsing gas prices in Europe have whacked Australian thermal coal, at a time when demand weakens after the winter heating season and Asian buyers typically shut power plants for maintenance.

While the International Monetary Fund this week cut its outlook for global growth on concerns over the effects of a long-running trade war between the U.S. and China, analysts say coal’s current collapse owes less to weaker economic activity than a slew of disparate market forces.

The European effect

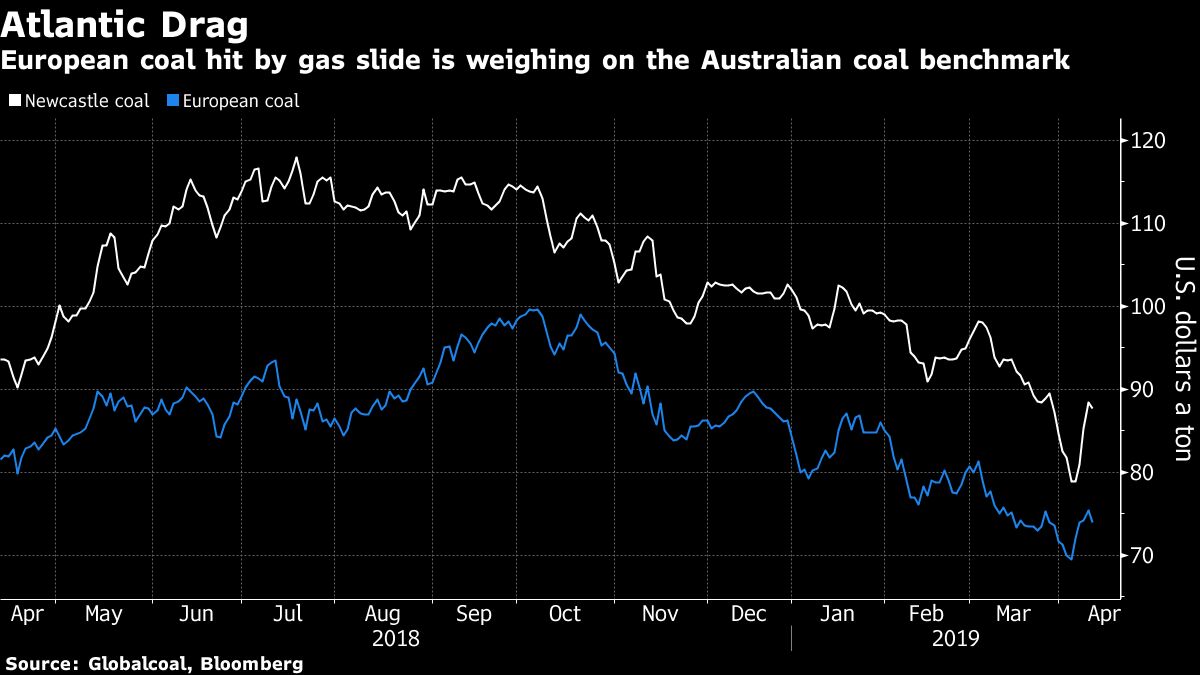

Coal prices at Newcastle in Australia — the world’s second-biggest exporter of the power-station fuel — slumped 20 percent from early March to the lowest level since 2017 on April 3. The fall can trace some of its origins to Europe.

European gas tumbled last month on an oversupply, subsequently dragging Atlantic Basin coal lower, which in turn weighed on Newcastle prices, according to Citigroup Inc. However, prices could start to recover as warmer temperatures boost air-conditioning use, according to Credit Suisse Group AG.

Opportunity for some

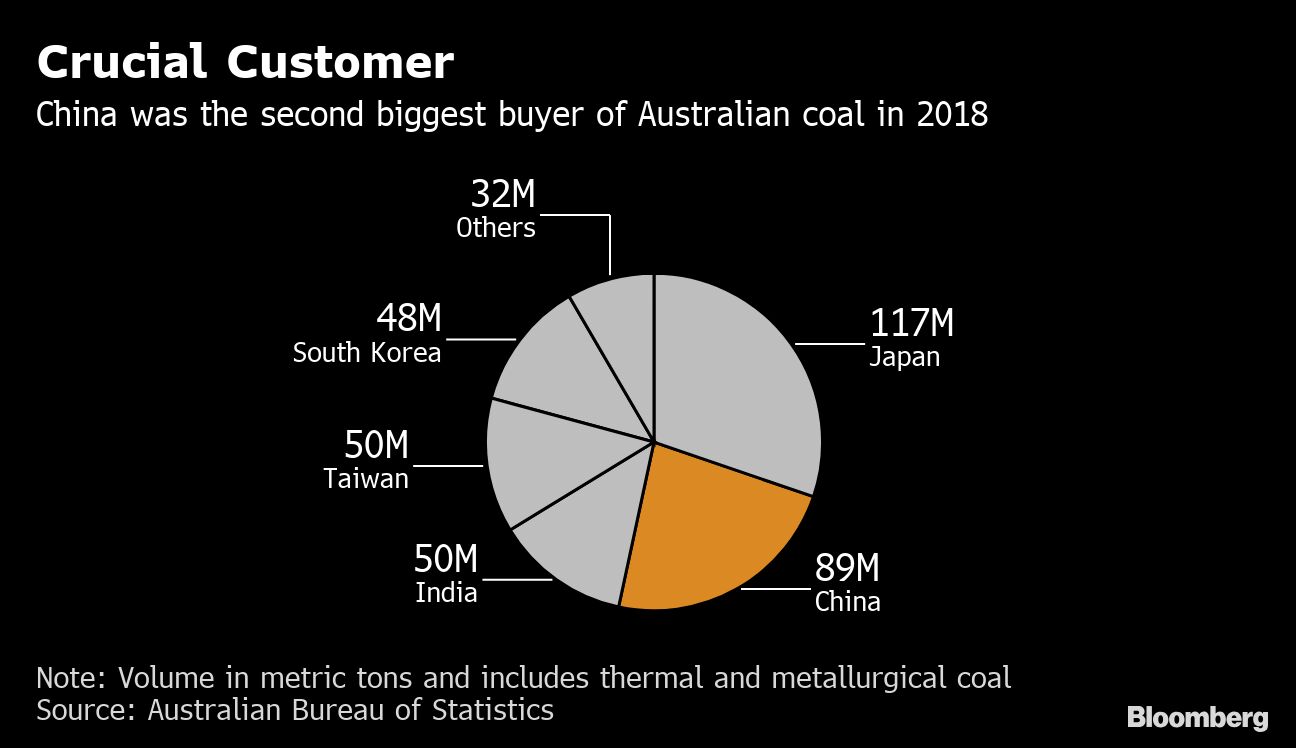

Newcastle’s slump is already crowning winners and losers. Global miner Glencore Plc last month locked in some annual volumes to Japanese utilities at about $95 a ton, prior to the steep price drop. U.S. exporters may lose out as they become priced out of the Asian market, according to Citigroup. The bank also predicts China may lift import curbs to access cheaper Australian coal if prices hold around current levels.

Speculation lingers

Lack of clarity over China’s import curbs has caused uncertainty in the market. Ongoing delays to Australian imports by the world’s biggest consumer has discouraged traders from ordering cargoes, according to Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

As speculation lingers about the Asian nation’s go-slow tactics and producers redirect shipments, Australian miner Whitehaven Coal Ltd. said Thursday that China’s policies are to support its miners, which came under pressure from lower domestic prices in 2018. Shares of producer China Shenhua Energy Co. have risen almost 5 percent this year, while Yanzhou Coal Mining Co. has soared nearly 40 percent.

Australia “naturally ends up the victim of what is essentially an attempt by the Chinese government to cap overall coal imports” to protect the domestic coal market, said Ralph Leszczynski, head of research at shipbroker Banchero Costa & Co. in Singapore.

LNG link

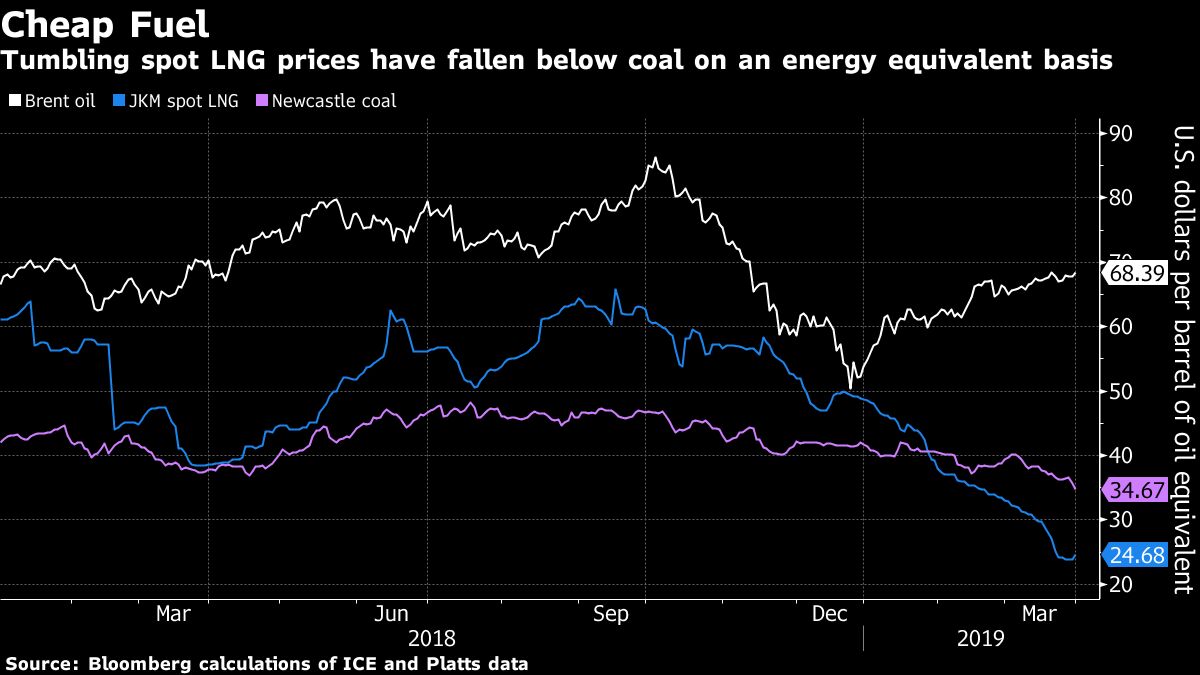

Royal Dutch Shell Plc last week agreed to sell liquefied natural gas to Tokyo Gas Co. at prices that include a link to coal, the world’s first such contract. By diversifying its price exposure for LNG, which has historically been linked to oil, the Japanese utility said it stabilized costs of the supercooled fuel.

If the trend catches on, coal may face even more pressure in some markets as gas generators are better able to compete with power suppliers using the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel.

“In Asia, gas is competing closely with coal in power generation,” said Xi Nan, a senior gas and power analyst with Rystad Energy AS. “However, we have started seeing dropping coal-to-gas switching prices since Q3 2018, suggesting that the two fuels are moving towards the same direction and not always in line with oil prices.”

Far from the end

The current collapse isn’t indicative of a global shift away from the dirty fuel. While cleaner energy sources such as wind and solar are making inroads into the power mix throughout Asia, they haven’t come close to ringing the death knell for coal, yet.

The fossil fuel will continue to be a key provider of heat and light through to 2040, according to the International Energy Agency, while BHP Group sees India and other low income emerging markets driving demand into the future.

(By Ben Sharples)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments