Breaking from the gold standard had disastrous consequences

|

About 100 years ago, in his testimony before Congress, banking giant J.P. Morgan famously stated: “Gold is money, and nothing else.”

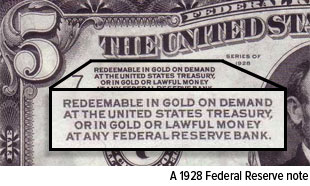

At the time, this was true in every sense of the word “money,” as the U.S. was still on the gold standard.

Of course, that’s no longer the case. Despite the fact that previous attempts in other countries to adopt fiat currency systems wreaked havoc on their economies, the U.S., under President Richard Nixon, cut all ties between the dollar and gold in 1971. Gold rose 2,330 percent during the decade, from $35 per ounce to $850.

Today, money supply continues to expand while federal gold reserves remain at the same levels.

click to enlarge

Many people still view the yellow metal as something more than just another asset. They also contend that it’s grossly undervalued. In a recent interview with Hard Assets Investor, author and veteran gold investing expert James Turk explained that the money we use now in transactions is not real money at all but a substitute for gold—real money—which he sees fundamentally valued at $12,000 per ounce.

That is to say, if the U.S. government decided tomorrow to return to the gold standard, one ounce of the metal could be valued as high as $12,000, according to Turk’s model.

The current fiat currency system in the U.S. is more than 40 years old. That’s much longer than many in the past lasted, including two of the earliest attempts by central bankers Johan Palmstruch and John Law, both of which I summarize below. Some readers might identify more than a few parallels between then and now.

Johan Palmstruch, the Dutchman Who Started a Paper Ponzi Scheme in 1661

|

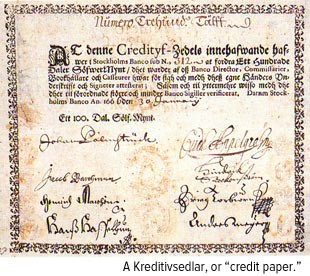

In the mid-1600s, a Dutch merchant named Johan Palmstruch founded the Stockholms Banco in Sweden, the first bank in Europe to print paper money. The Swedish currency at the time was the daler, essentially a copper plate. Palmstruch’s bank began holding these and issuing banknotes, which were exchangeable in any transaction and fully backed by the physical metal.

At least, that’s what customers were told.

As you might imagine, people found these notes to be much more convenient than copper plates, and their popularity soared. But there was one (huge) problem. Palmstruch had been doling out so many paper bills, that their collective value soon exceeded the amount of metal on reserve. When customers heard the news, a major bank run occurred, but Palmstruch was unable to honor the rapidly-weakening notes.

By 1664, a mere three years into his monetary experiment, the Stockholms Banco was ruined and Palmstruch was jailed—just as Bernie Madoff would be three and a half centuries later.

John Law, the Infamous Scottish Gambler Who Defrauded the French with Worthless Paper

A little over 50 years later, in the early 1700s, a similar experiment was conducted in France, with even more disastrous consequences. This time, the perpetrator was a Scottish gambler and womanizer named John Law, who as a young man had been forced to flee Britain after he killed a man in a duel over a love interest—and bribed his way out of prison. After escaping jail time, Law spent 10 years or so gallivanting about Europe and developing his economic theories, which he outlined in an academic paper.

It was the Age of Enlightenment, when great iconoclastic thinkers such as Descartes, Locke and Newton emerged, changing our understanding of consciousness, politics and physics. Baroque music was all the rage in Europe, as were composers like Bach, Handel and Vivaldi. It was also a golden age of get-rich-quick schemes, and as investors, it’s important that we be aware of the history of human behavior.

In 1715, France was insolvent. It had just lost its king, Louis XIV, and the Duke d’Orléans was named regent until the late monarch’s great-grandson came of age to rule. Familiar with Law and his unorthodox ideas, the duke established him as head of the Banque Générale in hopes that he might reduce the massive debt Louis XIV left behind.

To this end, Law began printing banknotes—lots of them—and flooding the economy with easy money. Doing so, he believed, would expand employment, boost production and increase exports.

|

It indeed had those effects—for a time. Paris was booming. The number of millionaires multiplied.

Unlike Palmstruch, Law made no claims that the notes could be converted back into gold or any other metal. He believed that a currency, whether gold or paper, had no intrinsic value other than as a government-sanctioned medium of exchange. Instead, his notes were “secured,” vaguely, by French land, including its colonies in the Americas. There was also no limit to the amount of money that could be pumped into the French economy. Like many of today’s central bankers, Law was of the opinion that if 500 million notes were good, a billion were even better.

But to make it all work according to plan, he had to take extreme measures. Law outlawed the hoarding of money, the use of coins and the possession of more than the minimalist amount of gold and silver.

The system turned out to be untenable and the paper money became worthless. After only four short years, the currency bubble burst. Law was not only removed from office but exiled from the country. Until his death in 1729, he roamed Europe heavily in debt, making his way by his former occupation, gambling.

The incident had long-lasting effects. It sustained the country’s economic woes for years and contributed to the start of the French Revolution later in the century, as it stoked working class disenfranchisement.

Lessons Learned?

Just as we still read Locke and listen to Bach, we should remember what Palmstruch, Law and other reckless central bankers did—which was essentially pull the rug out from under their countries’ monetary systems. It would be extreme to suggest that a similar collapse in currency might one day happen in the U.S., but it’s worth repeating that the gold supply has not kept pace with the money supply.

This could have huge implications.

As James Turk points out:

Eventually people are going to understand that all of this fiat currency that is backed by nothing but IOUs is only as good as the IOUs are good. And in the current environment, the IOUs are so big, a lot of promises are going to be broken.

Should those IOUs one day become as worthless as Palmstruch’s or Law’s paper—however unlikely that might be—I suspect many readers would feel relieved to know that they had had the prudence to invest in gold.

I always advise investors to hold 10 percent of their portfolios in gold—5 percent in bullion, 5 percent in gold stocks, then rebalance every year.

Tell us what you think!

All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the link(s) above, you will be directed to a third-party website(s). U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by this/these website(s) and is not responsible for its/their content.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments