Ink from ancient Egyptian papyri contains copper

A new study by researchers at the University of Copenhagen revealed that the brownish colour that shows up in many papyrus scrolls from ancient Egypt came from copper-infused ink, as opposed to just carbon ink.

Using advanced synchrotron radiation-based X-ray microscopy equipment, the Danish scientists were able to identify the presence of copper in inks written on 2000-year-old documents. This previously unknown component was likely an unintentional addition to the compounds and suggests that the pigments were obtained as a byproduct of sulfurous ore smelting.

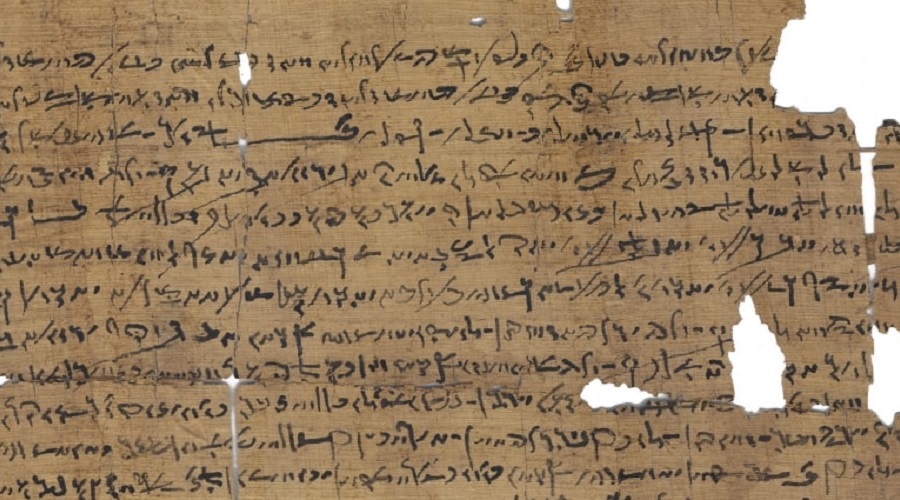

The researchers, led by Egyptologist Thomas Christiansen, reached this conclusion after analyzing the chemical composition of inks etched on fragments of the university’s Carlsberg Collection of papyri.

According to a press release issued by the university, the Carlsberg papyri were produced over a period of 300 years in different regions of Egypt and came from two primary sources. The first source was a man named Horus, a soldier stationed at a military camp in Pathyris (today’s Gebelein). His personal papers, some 50 sheets of Greek and Egyptian papyri, date back to the late 200 and early 100 BC.

The other source was the temple of Tebtunis (modern Umm el-Breigât,) the only known large-scale institutional library from ancient Egypt. An estimated 400-500 manuscripts were recovered from this site, spanning the 100 through the early 300 AD.

Yet, the composition of the copper-containing carbon inks showed no significant differences that could be related to time periods or geographical locations, “which suggests that the ancient Egyptians used the same technology for ink production throughout the country from roughly 200 BC to 100 AD,” Christiansen said in the institutional statement.

The main problem with these sheets -and the issue that inspired the research- is that they are poorly preserved and have broken down into smaller fragments. On average, only 10 per cent of each manuscript is likely to have been saved, making it very difficult and time-consuming to puzzle together individual parchments. The researchers hoped that by analyzing the inks, they could help quicken this reconstruction process.

They also expect their results to be useful for conservation purposes, as detailed knowledge of the material’s composition could help museums and collections make the right decisions regarding storage of papyri.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

RTS Support

Well the ancient ink doesn’t remove by simple water or alcohol. No wonder why ancient technology has more quality than now.